In this abridged interview with late Ikeogu Oke, published one year ago, the poet and winner of NLNG 2017 Prize for Literature provides some of the deepest insights yet into his life and work:

The Heresiad took you 27 years to write. Why did it take you so long?

Well, I worked on it for 27 years. This is how I calculate the duration. I moved to Calabar in 1988. At that time, I had taken a decision to become a poet, a career poet. And I moved into a house with my brother. We hadn’t even furnished the house. So, I spent most of the time on the floor. Then something happened. An author published a book that sparked controversy around the world.

What book was that?

Well, I wouldn’t want to be more specific than this. So, the book sparked controversy around the world and the author was condemned to death by some religious leader. And I wondered what could be in the book that would lead to the author being condemned? I got curious and somewhat sympathetic with the author.

The mere thought of his life being as risk ensured that. And there was the fellow feeling of a younger person what also had literary aspiration. I later had the opportunity to read an issue of TIME magazine that had the story as the cover.

How true is it that you have a sister whose name is Eresi and that the book’s name, Heresiad, came from her name?

Not at all. Actually, Heresiad is coined from heresy. That’s because the author whose experience triggered the poem was accused of heresy. But I had a sister called Eresi, which means, dove, in my Igbo dialect. She’s late; and I mourned her in a sequence of elegies entitled “A Fortnight of Memories” published in my second collection entitled Salutes without Guns.

So you sister’s name has nothing to do with the poem in anyway?

No.

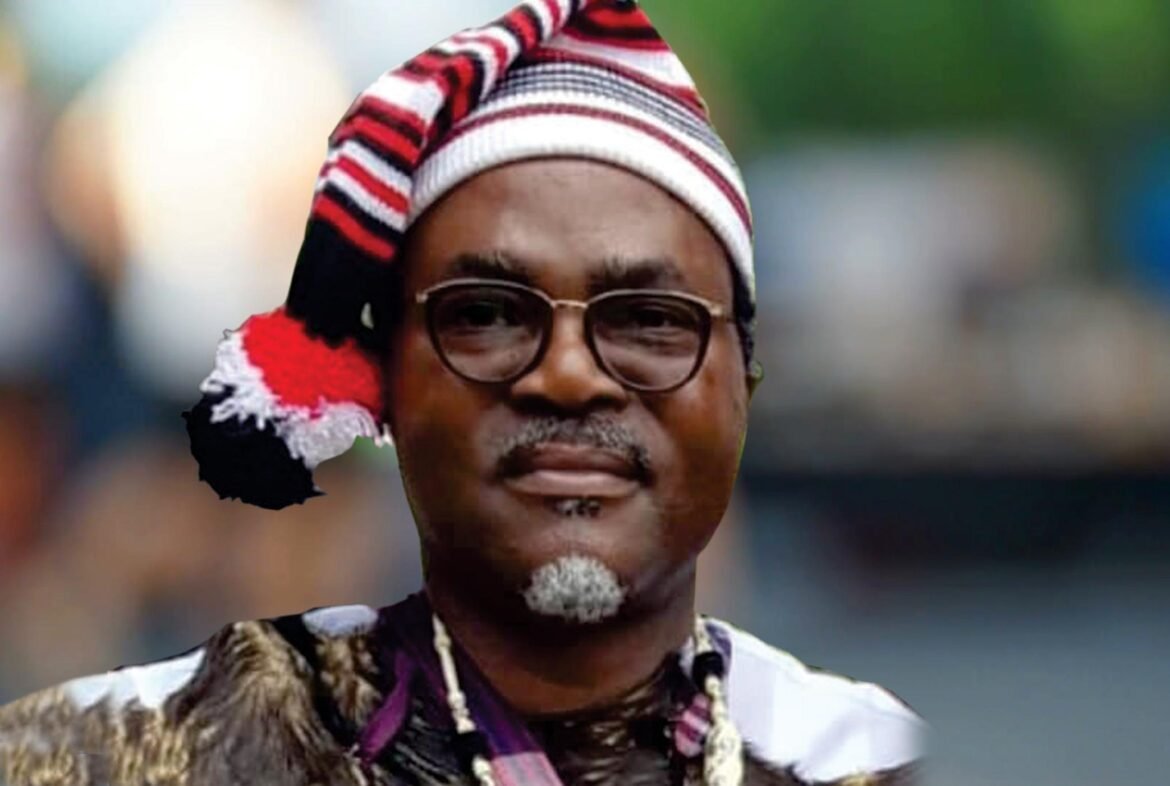

It took Oke 27 years to complete the writing of The Heresiad; / Photo credit:Ikeogu’s Facebook page

The poem has now won you a $100,000, how does that make you feel?

You know, it an amazing feeling. I mean, I’m gratified. But that’s not the kind of money I would think I couldn’t make. But I made it doing what I love. It brings a feeling that is almost difficult to describe. I couldn’t imagine such a thing happening when I started writing poetry.

I didn’t embark on a literary career with such an expectation. I didn’t consider writing as something from which I would make money, though my earliest published poems were paid for. They were published in an American magazine, Unity Magazine.

For each poem they accepted to publish, they offered me money, as far back as 1987. So, making money from my poetry isn’t something I wasn’t used to. But I wouldn’t have said pay me for it.

“I’m gratified. But that’s not the kind of money I would think I couldn’t make. But I made it doing what I love. It brings a feeling that is almost difficult to describe. I couldn’t imagine such a thing happening when I started writing poetry.”

How did you receive the news?

Well, I was at home. I was anxious. Like I said, I hadn’t planned the entire process. But winning became a possibility to me when I got to that last stage. So, I was coming back from somewhere that day the winner was announced. I had said I would get home and relax and wait for the news. Then I was at my desk working at home and also looking at my phone and then the news popped up on Facebook.

What was your immediate response?

Well, I had consciously planned to control my response. First, when I was coming home, I drove home quickly but slowly because in a way one could be killed by the joy of winning or the grief of losing. I simply drove home and calmly waited for the news. Of course when it came, I was excited. My household erupted in cheers. We were delirious.

Was there any time during the waiting period you thought you wouldn’t win?

I believed in my work. And I have read quiet a lot of poetry. I have done that for more than 30 years. I knew the quality of work I entered for the competition. I also had had people read it. So, I wouldn’t be surprised if I won the prize.

So, you never entertained any doubt?

No. No. No. There was going to be an adjudication by human beings who might see things differently. And I was willing to defer to their decision as judges. But deep down, I knew that I wouldn’t be surprised if I was pronounced the winner, considering the quality of my work. I wasn’t surprised that the judges’ pronouncement met my expectation.

What would you say to the other two finalists?

I think they are fine, committed poets. It is just that the judges didn’t choose their work as the winning entry.

When exactly did your interest in writing begin?

It was shortly after I left secondary school in 1984. My father wasn’t educated. He barely went to night school. In fact, I think he hated having not been educated. As a result, he came to love books deeply and somehow tried to acquire the ability to read and write passably.

So, you may say he educated himself. From his example, I came to love books too. So, he encouraged me and inculcated in me a very deep love for reading books. In our house then, we had a shelve with an array of books.

And there were issues of Unity Magazine and a children’s magazine called Wee Wisdom for which he subscribed. Unity Church, a more handy abridgement for Unity School of Practical Christianity, was the church he attended then which he was taking me to as a child.

The parent institution, founded in 1886, and called Unity School of Christianity, in based in Kansas City, Missouri, USA. They published Unity Magazine and Wee Wisdom. So, one day, after I finished secondary school, I picked up one of the magazines and I saw a poem entitled “Buoyed by Prayer” by one Winifred Heinskin Layton. I’m not sure I spelt the middle name correctly. I read it and it charmed me.

Ikeogu Oke is known for performing his poems in his native Ohafia war custom / Photo credit:Ikeogu’s Facebook page

Who inspired you the most?

I will give that to a great number of poets. I began by reading the Romantics. Yes, I read Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron. Then, I moved to the classics: Homer, Virgil, Dante, Chaucer, Milton, Goethe, etc.

Then some American Poets like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman and the French poet Charles Baudelaire.

Then the Irish poets W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot and the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore and Joseph Brodsky. I also read Pushkin, then Alexander Pope and Thomas Gray.

Then I had a particularly auspicious reading of Niyi Osundare’s The Eye of The Earth around the time I conceived The Heresiad.

I found the balance it struck between aesthetic and moral tendencies very interesting and wanted to reflect that in The Heresiad. I think each of these poets and many others I have read have influenced me somehow.

Would you say writing is profitable in Nigeria?

It depends on the kind of profit you are looking for.

Well, is it something one can live on?

It depends. You see, I believe one can live on writing. There are types of writing that if you do them well and you are strategic in the way you ply the trade, as it were, and the way you utilize the opportunities you get, your talent and other related resources, then you can live on writing.

The cover concept of a bird on the brook, I have wondered, can you tell us more about that?

The cover comprises symbols of ideas explored in the book or its thematic preoccupations. These include freedom of expression, freedom of thought, intellectual and creative liberty. There are several others.

Then the blazing sword descending on the dazzling book, a symbol of knowledge, is a symbol of violence. So there’s also that joint symbolism of a clash between the book and a sworn enemy as you might consider Boko Haram.

But the sword could also be a symbol of justice…

Rarely is it so. And not in this context. Then, the dove, brings peace upon the conflict.

That’s mercy

Just a white door bringing peace upon the conflict. But then the poem urges mercy for the condemned author.

Many think that the art of creative writing is dying. Do you also think so?

I don’t think so. I have earlier said that things like this NLNG Prize have contributed to keeping it going. But there are issues because of our values as a people.

You do you consider the significance of the NLNG Prize?

There is something that happens through literature all over the world. I call it the phenomena of a tree making a forest. Literary worlds often develop around individuals, the likes of Shakespeare, Goethe, Cervantes, Tolstoy, etc.

Such are the single trees that have become vast literary forests, extending beyond their native countries to all parts of the world.

believe the prize has the potential for uncovering such trees that can make a forest and bring global and lasting honour to our country like those trees that can make a forest in literature. But even as things stand, it is making a positive impact by stimulating and rewarding literary creativity.

We cannot all watch our society devolve into crass philistinism. And I think this prize is a genuine intervention against such cultural degeneration.

“Literary worlds often develop around individuals, the likes of Shakespeare, Goethe, Cervantes, Tolstoy, etc. Such are the single trees that have become vast literary forests, extending beyond their native countries to all parts of the world.”

Some would say that this kind of money, energy and the research would be better devoted to science?

Well, science is very important. But I think we have enough resource in the country to support both the arts and the sciences. I don’t think one should take the place of the other. It is desirable to have prizes for the sciences also.

Tanure Ojaide, with his book, Songs of Myself, was your closest competition. What do you think about him?

You know, I think he put in his best. I am familiar with his poetry. I have been for a while. He is my senior friend, if I may put it that way. In fact, when I lived in Calabar, before I enrolled as an graduate, I read his collection, The Fate of Vultures.

Then I responded with a poem entitled “Apologia”, a defence of the vulture from the opprobrium the world normally heaps on it apparently without reflection. I thought: What is the vulture’s sin that everyone calls it a bad name?

I compared the vulture with the much-admired eagle.

The vulture is an avian undertaker, disposing of dead bodies by turning its stomach into a cemetery of sorts. That’s some useful service to nature that hurts no one. Yet everyone maligns it. But the eagle is a killer, a murderer, a ruthless predator, plundering life out of less strong and mostly defenceless animals.

Yet it is the “king of birds” that everyone would rather be like if they could be birds. If human kings were to be brazenly predatory like the eagle, hunting and killing their subjects at will for food, I’m sure their victims and other subjects won’t find their royal cannibalism acceptable.

But we admire the eagle with its murderous life and despise the vulture that waits for things to die before eating them and do not realise the immorality of our affection for the one and the unfairness of our antipathy towards the other.

That’s my argument in the poem in response to Ojaide’s The Fate of Vultures. I am familiar with his work. He put in his best. Just that I write poetry differently from him. I think he is a committed poet.

What inspires you to write: joy, sorrow, tragedy?

Everything!

Is any of your children taking after you?

Yes, my first daughter

How old is she?

She is nine. And sometimes she writes things I find remarkable.