In what could be his most detailed interview so far, US-based journalism teacher and critic, Farooq Kperogi, speaks on a wide range of issues from his hard-hitting columns to journalism in Nigeria and from Atiku Abubakar to Sowore’s detention and the Buhari-Tinubu relationship. It’s as hard as nails, and yet, clear as crystal. Once you start reading it, you can’t stop:

In one of your recent articles, you described the government of President Muhammadu Buhari as a “familocracy,” and cited a few examples of his relatives in top government jobs. Some would say you paid more attention to filial ties than to competence. In any case, they are Nigerians. Do you agree?

Presidential nepotism didn’t start with Muhammadu Buhari, for sure, but it deepened, widened, broadened, and lengthened in both magnitude and severity with him.

That fact, in and of itself, is deserving of censure.

But it’s worse: he is the first elected Nigerian leader to publicly avow that his family members would not participate in his government.

He got a lot of brownie points for that from several people, including me.

He didn’t have to say that, but he did, so it’s fair to hold him to his promise, to the terms of his unsolicited commitment to exclude his family members from his government.

It’s not accurate that in my column I was more fixated on the familial ties of Buhari’s relatives in his government than I was on their competence.

Take Sabiu “Tunde” Yusuf, for example. He is Buhari’s Private Secretary.

I pointed out that he had never had any formal work experience before 2015.

He is a 30-something-year-old recent business administration graduate who used to sell phone recharge cards in Daura until 2015.

He neither has the experience nor the training to be a presidential private secretary.

Compare him to Olusegun Obasanjo’s Principal Private Secretary, Stephen Osagiede Oronsaye, who was an accomplished chartered accountant that rose to the position of a Director in the Federal Ministry of Finance in 1995 before Obasanjo appointed him as his Principal Private Secretary.

Or Ambassador Hassan Tukur, Goodluck Jonathan’s Principal Private Secretary, who was a retired diplomat before his appointment.

Most important, though, both Oronsaye and Tukur are not only unrelated to the presidents they served—they’re not even from the same states or ethnic groups as the presidents they served— they were qualified for the job.

It’s an entirely different matter, of course, if they did their jobs well. But the point is that what Buhari has done is unmatched in Nigeria’s history.

Almost all the Buhari family members who work in the Presidential Villa had no formal work experience before 2015.

Even Abdulkarim Dauda, Buhari’s Personal Chief Security Officer and nephew, who seems marginally qualified for his job, was undeservedly given triple promotions in the space of three years to justify his position.

What is worse, Buhari personally wrote to the Nigeria Police in October 2019 asking that his nephew’s service be illegally extended to May 13, 2023 even though he was supposed to retire this year, having served in the police for 35 years.

This sort of audacious, in-your-face nepotistic excess is unprecedented.

I have never met Atiku Abubakar in my life and have never had any formal or informal association with him. I was never hired by anyone to do anything. No one on earth is rich enough to buy my conscience, not because I am stupendously wealthy but because I cherish my independence. I am unpurchaseable

You recently expressed concerns about the safety of your family members in Nigeria after an exchange with an associate of the Buharis over a post on Mamman Daura’s birthday party in the UK. Has the matter been resolved?

The person who threatened me is actually Mamman Daura’s son-in-law by the name of Inua Bello Anka.

He said the video of Mamman Daura’s lavish London birthday party at a pricey hotel that I shared on my Twitter and Facebook timelines has his two children in it and that I should take it down because of “security issues.”

When I didn’t oblige him, he threatened that I “won’t get away with this” and that I had “no idea what you are dealing with.”

I told him if his threats meant that he would sue me, I was ready for him.

But just in case he meant that he would harm my family members in Nigeria, I took a screenshot of his threats and shared them on social media and on my blog so that the world would know.

If it was just an impotent intimidation tactic, well it’s all out there. But nothing has been resolved.

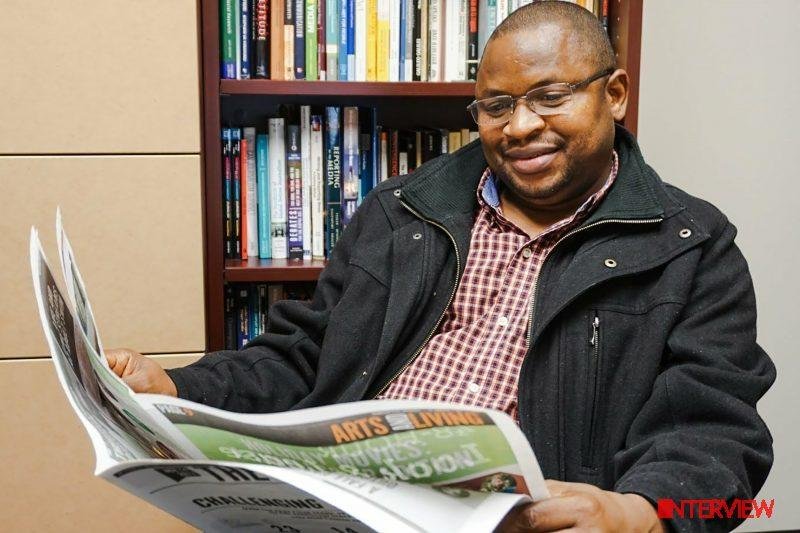

Farooq Kperogi: I have consistently been critical of every government in power since 1999 / Photo credit: Kperogi

Do you sometimes worry that your articles could put your family in Nigeria in danger? Do they call you to “tone it down?”

Everything we do in life comes with a risk.

People who shy away from doing what they believe is right because of the dread of risks have no courage of their convictions.

I am not that kind of person.

And yes, family members have told me to stop commenting on the malfeasance of the Buhari regime.

But that won’t stop me.

In 2017, the emir of my hometown summoned the entire emirate council, invited my uncle to the palace, put a call to me, and told me I was on speakerphone.

He proceeded to tell me that the entire community was appealing to me to stop my critical commentaries on Buhari.

I asked the emir why he never once called to say I should cease writing critical articles against Goodluck Jonathan because I was just as critical of Jonathan as I was (and still am) of Buhari.

He was quiet. I told him I had an answer: religious and regional bigotry.

He was offended. And that ended the call— and the entreaties.

At the height of the 2019 general elections, some said the opposition, specifically, former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, hired you. Is that correct?

I have responded to this allegation countless times in my columns and in my social media updates.

I have never met Atiku Abubakar in my life and have never had any formal or informal association with him.

I was never hired by anyone to do anything.

No one on earth is rich enough to buy my conscience, not because I am stupendously wealthy but because I cherish my independence.

I am unpurchaseable.

When I gaze at reality, I make self-conscious efforts to ensure that my judgments are not mediated by the primordial, geographic, cultural, religious, etc. lenses that come to people naturally, but by my sense of what is true, just, and fair.

I have consistently been critical of every government in power since 1999.

The records bear me witness. It’s nothing more than the good old philosophy of holding people in power to account.

Did the opposition— or Buhari—hire me when I put Obasanjo’s and Jonathan’s feet to the fire before Buhari’s ascendancy to the presidency?

Why can’t people understand that there are people who have a sensitive moral conscience, who are actuated by higher ideals, who are not given to crass mercenariness, who are too conscious of their own unconscious to avoid falling prey to the easy lures of instinctual, reactionary identity politics?

The answer lies in something psychologists call projection: the subconscious psychological process that disposes people to attribute to others the unconscious negative traits and emotions that dwell in them.

It’s morally degenerate dissemblers who accept money from politicians—or who are disposed to accepting money from crooked politicians to deodorise the politicians’ ethical stench—that accuse others of doing so without a shred of evidence.

They are projecting their moral fragility, ethical rottenness, and lack of principles onto others.

Omoyele Sowore would be my person of the year. He forwent his comfort to confront Buhari’s monster of fascistic executive overreach and is living, at least for now, to tell the story

Is there any candidate you would have personally endorsed for the presidency in 2019? Why?

Almost any other candidate would have been better than Muhammadu Buhari.

Well, I am not important or influential enough for my endorsement of anyone to be of any consequence.

But even if I were a consequential political player whose endorsement had the capacity to sway people, I wouldn’t have endorsed anyone.

I am generally wary of everyone in power.

As American journalist Lincoln Steffens once said, “Power is what men seek, and any group that gets it will abuse it. It is the same story.”

My job is to hold people in power to account.

I won’t endorse anyone that I would most certainly clash with as soon as they get on the saddle of the presidency.

I wrote a widely shared column titled “How Political Power Damages the Brain—and How to Reverse it” where I shared a research that says people in power literally suffer brain damage.

Unfortunately, for reasons I am yet to fathom, many people who share the column on social media now take my name out and attribute it to Pat Utomi even though the very first sentence of the column reads, “I was one of seven professors who facilitated a leadership training in my university here in Georgia for local government chairmen from a major Nigerian southwestern state”—and Utomi doesn’t live in Georgia.

The Buhari regime will go down in history as Nigeria’s most brutal civilian constrictor of the deliberative space

In one of your posts during the 2019 elections you used the photograph of a woman, with the caption, “thumb-printing on an industrial scale.” ICIR later fact-checked the picture as “fake.” You described the fact-check as “hatchet job.” Is it correct to say that you wrote INEC off, even before the election was conducted?

It was not a picture. It was a video. And it was as real as you can get.

It was a trending video of unidentified INEC officials who were caught thumb-printing ballot papers on behalf of APC.

The so-called fact-check didn’t deny the authenticity of the video; it only said the video was from the 2015 election.

But I never mentioned anywhere that it was from the 2019 election.

The so-called fact-check said I “implied” it was from 2019. How do you fact-check what’s in someone’s mind? What resides in my mind isn’t publicly accessible and therefore isn’t amenable to a fact-check.

A video of INEC officials thumb printing ballot boxes on a mass scale on behalf of the ruling party (the fact-check claimed it couldn’t ascertain that APC was the beneficiary of the thumb-printing even though it was apparent to even a careless observer that it was APC) is interesting any day, particularly at a time when the same party was perpetrating the same sort of electoral heist in many parts of the country.

It was a sponsored piece. And there were at least three dead giveaways to betray this fact.

One, the mercenary, ill-trained hustlers who wrote the report don’t work for the ICIR.

The lead writer of the piece, called Damilola Banjo, introduced herself to me as a reporter for Sahara Reporters.

I sent her questions to Omoyele Sowore and asked if he knew her. He said he did but added that he wasn’t aware that anyone was working on a story like that.

He later said she was “commissioned”—and that was his exact word— by some people to write the piece.

Sahara Reporters, for which she works, refused to publish it.

So she took it to the ICIR, which she doesn’t work for.

ICIR obviously has no standards, so it published it.

Second, the so-called fact-check only isolated instances of what it called misinformation by the opposition.

It ignored APC’s systematic, well-funded misinformation and disinformation campaigns.

For instance, the Buhari regime hired a rogue Israeli company to spread fake news during the election.

Its fake news campaign was so appalling that Facebook banned it—after the fact, of course.

A May 17, 2019 Associated Press news story titled “Israeli Disinformation Campaign Targeted Nigerian Election,” said, “One of the pages that Facebook cancelled appeared filled with viral misinformation attacking Abubakar, the former vice president of Nigeria.

The page’s banner image showed Abubakar as Darth Vader, the Star Wars villain, holding up a sign reading, ‘Make Nigeria Worse Again’.”

The AP story added: “The report also featured a page that explicitly lionised and boosted Buhari, with amateur videos eulogising the accomplishments of his presidency as though he were not locked in a tight battle for re-election.”

The third giveaway is the crude, juvenile name-calling in the so-called fact-check. Fact-checks usually just correct misinformation and leave it at that.

As I pointed in my initial response to the screed, their so-called fact-check was gratuitously abusive and opinionated and was unmoored to even the most basic requirements of journalistic integrity.

It imputed motives to me and divined motivations for my action. Fact-checks are usually, well, factual; they present information in a neutral, unemotional tone. Most important, though, I had been told the smear was going to come weeks in advance, so I wasn’t surprised. It’s part of the price for calling attention to Buhari’s incompetence and tyranny.

There is growing concern that the Buhari government is restricting the freedom of expression; some have even expressed the fear of a return to military-era dictatorship. Do you share this concern and why?

Yes, I do.

And I have written scores of columns and social media updates on this.

The Buhari regime will go down in history as Nigeria’s most brutal civilian constrictor of the deliberative space.

Why is this so? Well, it’s because the Buhari regime is intensely self-conscious of its illegitimacy, and, historically, all illegitimate regimes are repressive.

There is a direct relationship between a government’s self-construal of its legitimacy—or lack thereof— and its toleration of dissent.

The more illegitimate a regime is, the less tolerant it tends to be of opposition and notions of radical democratic citizenship.

British philosopher Bertrand Russel once said, “Freedom of opinion can only exist when the government thinks itself secure.” You can’t blatantly rig an election that you clearly lost and feel secure.

Your column in Trust was stopped under very controversial circumstances. Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently?

I wouldn’t have done anything differently.

I am actually glad I no longer write for the paper.

I have no capacity to function optimally in any environment that gives comfort to oppressors, that incubates bigotry, that fertilises rank hypocrisy, that nurtures unreasoning ethno-regional and religious solidarity with an effete tyrant, and that attempts to dictate the contours of my thought-processes.

That was not the Trust I knew and worked for.

The Trust I worked for was courageous, fair, just, tolerant, and accepting of diversity in more ways than most media houses in Nigeria.

For instance, in 1998 when Abacha’s fascistic fury was at a crescendo, Trust gave voice to critical opinions against Abacha.

But it suddenly became a pitiful poodle for Buhari and a tormentor of his critics.

For the first time since I started writing my column, I started receiving periodic emails from the Editor-in-Chief telling me—and, apparently, other columnists—how I should write and not write my column.

This started in 2016. I found the meddlesomeness both infantilizing and grossly unprofessional.

I knew I wouldn’t last much longer there, so the stoppage of the column didn’t come to me as a surprise.

In fact, I am surprised that I lasted as long as I did.

In September 2017, a shareholder in Trust sent me an email saying I was too “obsessed” with Buhari and suggested that I stop writing about him.

I reminded him that I was the first person to call Goodluck Jonathan “clueless”—I called him “unfathomably clueless”— when he visited America as an acting president.

I also called him a “highly credentialed ignoramus,” among other choice epithets, to the applause of people who now fanatically support Buhari and think he is beyond reproach or ridicule.

I told him no one in Trust ever told me I was “obsessed” with Goodluck Jonathan when I wrote column after column on his failings as a president. He had no comeback.

There is nothing I’ve written about Buhari that I haven’t written about people who preceded him. It comes with the territory. If he can’t stand the heat, he should get out of the kitchen

As a journalism teacher, what do you think are the three biggest threats to independent, credible press in Nigeria today?

The first threat, in my opinion, is the absence—or inadequacy—of independent source of revenue.

The Nigerian press is disproportionately dependent on government advertising to survive.

That isn’t good. Governments will always want reciprocal favors for their advertising patronage in fawning, uncritical coverage.

The second threat is ignorance. Most people who practice journalism in Nigeria today, sadly, are deficient in basic journalistic literacy.

I’ll highlight only two.

Most journalists, from my experience, don’t even know what constitutes libel, much less what legal defenses are available to journalists who are accused of libel, so they are easily intimidated into unwarranted self-censorship by the empty threats of libel lawsuits—by what Americans call SLAPPs, that is, Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, which are frivolous lawsuits that dishonest politicians file to bully and hush up journalists.

Many journalists could also use some good old precepts of accuracy, acknowledging sources of news, etc.

I have written about how well-regarded newspapers in Nigeria habitually lift stories from social media without acknowledgement and without independent verification.

This hurts the professional authority and symbolic capital of journalism as a whole.

The third threat I’d mention is what seems to me the progressive erosion of the virtues of principled distance from, or critical engagement with, government.

American journalist Finley Peter Dunne is famous for saying that “the job of the newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

It seems to me that the Nigerian press, for the most part, especially in the last four years, has imposed on itself the role of the comforters of the comfortable. Of course, there are a few honourable exceptions.

You used to be a supporter of President Muhammadu Buhari. What went wrong?

I was never a supporter of Buhari—or, for that matter, any politician. Occasionally expressing opinions that were congruent with Buhari’s didn’t suggest that I supported him.

As I always say, my loyalty is to principles, not to personalities. Personalities come and go, but principles are constant.

In my criticisms of the administrations that antedated Buhari’s, I sometimes appeared to be supportive of Buhari—just like some people think I support Atiku Abubakar now—because his position as an opposition politician caused him to express opinions that were consistent with mine.

I generally tend to support the underdog against the top dog.

Had Atiku become president, I would also most definitely have been asked why I no longer supported him because, as sure as tomorrow’s date, he would have been caught in my cross hairs.

I will always hold every power holder’s feet to the fire.

Nonetheless, even though Buhari and I saw eye to eye on some issues while he was in opposition, I had cause to, in a 2003 article, call attention to his inveterate bigotry and narrowmindedness.

The Buhari/Tinubu alliance would crack more noticeably. The people who prop Buhari in power don’t want Tinubu—or anyone outside their primordial constituency—to succeed them. That’s my prediction

You have repeatedly said your criticisms of Buhari and his government are not personal – they are vital to hold the government to account. How do you draw a line between such criticisms and personal attacks on him?

I don’t know what you mean by personal attacks. Buhari’s actions and inactions have consequences for millions of Nigerians at home and abroad.

There can be no expectation of a “personal space” for a person who occupies such a position. It’s therefore a misnomer to characterise anything said about Buhari as “personal.”

Everything about him is invariably public for as long as he rules from the Presidential Villa.

People who want to be spared from what you call “personal attacks” don’t run for public office; they stay in their personal spaces.

There is nothing I’ve written about Buhari that I haven’t written about people who preceded him. It comes with the territory. If he can’t stand the heat, he should get out of the kitchen.

If you were to make a prediction about the political landscape in 2020, what would it be?

I have no—nor do I believe anyone has—oracular powers, but I think 2020 would witness the incipience of the alignment of political forces preparatory to the 2023 election.

The Buhari/Tinubu alliance would crack more noticeably. The people who prop Buhari in power don’t want Tinubu—or anyone outside their primordial constituency—to succeed them. That’s my prediction.

Who is your person of the year (2019), if any, and why?

Omoyele Sowore would be my person of the year.

He forwent his comfort to confront Buhari’s monster of fascistic executive overreach and is living, at least for now, to tell the story.

He refused to give in when several interest groups prevailed upon him to compromise. He stuck to his guns, and he has now been released from illegal confinement (this comment was before Sowore was re-arrested).

In this season of mass authoritarian hypnotism in Nigeria, that’s worthy of admiration and praise.

One recent survey said Nigerians spend about half a billion dollars to send their children to schools in the US annually. What do you think can be done to cut this down?

I have no problem with private people sending their children to school abroad.

It’s their prerogative.

What I have a problem with is government officials using public funds to send their children abroad while universities at home decay and crumble.

Unfortunately, nothing can be done to stop it because Buhari who should stop it is its worst culprit.

People in government have no incentive to improve the quality of public schools in Nigeria because their children don’t attend those schools anymore.

Under what conditions would you accept a teaching appointment in Nigeria?

I’d love to come back to Nigeria at some point in the future to teach— with no conditions attached. Nigeria is, after all, my country of birth and where my heart is.

In a recent controversy involving Femi Fani-Kayode, you went into history to explain the etymology of the word, “Yoruba”, which Fani-Kayode said was a Hausa counterfeit. Do you think he was just been provocative or mischievous?

I frankly don’t know. But I’d guess that he shared what he knew and believed to be true. I hope, however, that he now knows better than to say that the ethnonym “Yariba” was “given” to the Yoruba by the Fulani. It’s wholly untrue.

What motivates a writer? The urge to mirror, influence and possibly, shape society? Iconoclasticism? Or what?

I think it’s all of that.

For me, my writing is animated by didactic, pedagogical, moral, and professional journalistic impulses.

I write political commentaries because I feel an abiding obligation to hold political leaders to account.

An English proverb says the onlookers, not the participants, see most of the game.

As I’ve pointed out in the past, coaches and technical advisers are needed in games not because the coaches and technical advisers are better than the players—several coaches and technical advisers, in fact, don’t have half the talent of players— but because the coaches and technical advisers have the benefit of technical knowledge and, most important, critical detachment from the field of play.

I am by no means a coach of people in power, but my critical distance from the field of power play allows me to see what people ensconced in the easy chairs of power don’t and probably can’t see.

This is true of most writers who are wedded to notions of critical democratic citizenship.

People in power need critical, independent voices to call attention to their abuse of power, not be their praise singers, in the interest of the society.