A familiar happy story in Nigeria: a 16-year-old graduating from a pricey private university, a 14-year-old accepted into medical school, a 16-year-old defending a thesis while classmates elsewhere are still navigating puberty.

Different universities. Different disciplines.

Parents with the same delusion. Young. Rushed. Immature. Unready.

Social media celebrates each case as a triumph: a genius child, exceptional parents, a family blessed.

But line them up side by side and the pattern is too deliberate to ignore.

These aren’t victories; they’re casualties. Lecture halls, convocation grounds, graduation ceremonies. Nothing is sacred. Most people want the same thing.

Nigerian parents are following the same playbook and the script ends with degrees on the wall and young adults who are academically certified but emotionally hollow.

Parental pride, the foundational problem.

Strip away the ceremonies, the Facebook posts celebrating “youngest graduate,” the WhatsApp forwards boasting university admission, and what you see is a nation that cannot live with patience, with developmental pace, with the ordinary timeline of human maturation.

Nigerian parenthood was built on the currency of comparison, the race to outpace neighbours, “keeping up with the Joneses,” the need to have something extraordinary to announce at “owambe” parties that the next person envies.

When that rush meets a child’s fragile development, destruction takes its place. And that destruction, when combined with falsified birth certificates and private schools willing to accelerate anyone for the right price, becomes inevitable.

So, I ask: when will Nigerian parents evaluate their values in this race to nowhere?

Parents are not the inventors of ambition, but they its most zealous disciples. They take developmental milestones and convert them into competitive sport.

They tell their children that being normal is failure, that patience is laziness, that maturation can be microwaved.

Many Nigerian parents baptize their desperation as excellence, their ego as investment in the future.

Parents are willing and eager to hand their kids the permission slip to skip childhood.

They turn adolescence into a race, their child’s emotional health into collateral damage, and their pride into applause at graduation.

I wouldn’t be writing about this if I had no experience.

My dad trained and worked as a teacher for decades. But I didn’t start primary education until I was almost seven.

He didn’t rush me.

I think that factor enabled me as a high achiever in primary school, because by Primary Four, I was already admitted into a secondary school – St. Charles Grammar School in Osogbo.

Ignoring the advice of his friends, my dad insisted I wasn’t prepared for secondary education. In Primary Five, I passed the Common Entrance Examination for prime schools, and was also admitted by Osogbo Grammar School.

This time, he allowed me to attend the other school because he didn’t think I was mature enough to attend boarding school outside of his parental supervision. I schooled where he was a teacher as a day student.

Some kids collapse under workplace pressure within months; others retreat into extended adolescence, unable to navigate independence

I had skipped the final year of primary education and it took me at least three years to recover. I really didn’t start doing well academically until my fourth year in secondary school. Skipping a class left an impact on my progress.

In Nigeria today, if a 14-year-old genius scored 320 in JAMB but faced the university age barrier, instead of a collective pause to consider whether college was appropriate for someone who is almost a child, the nation would erupt in outrage – not at the pressure on the child, but at the policy preventing immediate admission.

And it wouldn’t be out of concern for a gifted student’s well-being; it would be fury that bragging rights were being denied.

Parents survey admission policies, obsess about their child’s scores, and turn cognitive precociousness into a weapon.

Whether on WhatsApp, in a family living room or in the news media, the impulse remains the same: make sure everyone sees our child as exceptional, no matter the cost.

This is why so many of these “success stories” end with young graduates who crumble in the workforce or struggle with basic adult functioning.

Employers, especially at the multinationals, consistently note that despite holding degrees, many Nigerian graduates are emotionally stunted, socially awkward, professionally inept.

Some kids collapse under workplace pressure within months; others retreat into extended adolescence, unable to navigate independence.

Those sent abroad frequently fail to become responsible adults.

Even those who survive professionally often admit they sacrificed critical developmental years. They weren’t trying to build careers; they were trying to satisfy parents who needed proof of exceptionalism.

Instead of a natural progression through life stages, it’s a forced march through certificates. It’s development weaponized into competition.

It’s the Nigerian parent deciding that if their child must grow up, it will happen at twice the speed so the family name gains currency.

The degrees aren’t just academic credentials; they’re family bragging rights.

And the Nigerian government lets them do it, when most other governments don’t.

The school system in America would not compromise strict rules about standard education age when my son fell into a disadvantage for being born in January.

They would not allow him to be in the same class as someone born in December.

Interestingly, former U.S. President Barack Obama allowed his daughter, Malia, to delay attending university by one year by taking what is known as a “gap year” after being admitted to Harvard University in 2016.

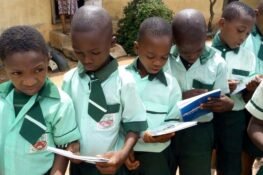

While children in developed nations are protected by age-appropriate educational standards, Nigerian kids are given the shortest childhood.

Their developmental needs are dismissed, their immaturity rationalised, their silent suffering overlooked by a society that calls rushing them through school “pushing for excellence” instead of what it is: state-sanctioned child abuse!

When JAMB began enforcing the 16-year minimum age policy, a pressure group called the Movement against JAMB Injustice – ostensibly concerned parents – protested angrily.

Parents didn’t just complain; they organized, petitioned and appeared on public broadcasts denouncing what they called oppressive government policies.

Eventually, the government caved in to parental pressure.

It is difficult to understand why parents in modern Nigeria need educational achievement as a status marker.

Our new culture could not see premature graduation as harmful to children. It sees it as proof of superior parenting.

The belief that educational credentials have great value has become a misplaced obsession.

The cultural premium placed on titles became the fetishization of youngest graduates.

The parental need for validation became superior to the child’s welfare.

That’s why the same society that would call a 14-year-old getting pregnant “a tragedy” will call a 14-year-old entering university “a prodigy.”

Nigeria’s educational pressure doesn’t just damage the children rushed through it; it creates ripple effects throughout society.

Employers inherit graduates who can recite textbooks but cannot think critically. Workplaces become remedial schools where 20-year-olds must learn emotional intelligence and professional communication.

Universities lower standards to accommodate immature students.

And the cycle continues because the system profits from it: private schools charge premiums for acceleration, exam bodies collect fees from younger test-takers, parents maintain their bragging rights, and children – well, children pay with their mental well-being.

What international standards understand is that education isn’t just about reading books.

It’s more about developing humans.

In the U.S., UK and across Europe, students typically enter university at 18 or older, not because those societies are slow, but because they understand that cognitive development, emotional regulation, identity formation, and social maturation happen on biological timelines that cannot be rushed.

Adolescence exists for a reason.

The brain doesn’t finish developing until the mid-twenties.

Skipping stages doesn’t accelerate maturation; it creates developmental gaps that haunt people for life.

Nigerian parents look at these systems and see inefficiency.

They have no respect for childhood.

Nigeria is enacting a slow-motion tragedy written in the currency of parental ego.

Every rushed graduation is another child sacrificed; another developmental stage skipped.

And the country keeps pretending the cost doesn’t exist.

Until Nigeria is ready to value its children’s well-being over its parents’ pride, the damage will not stop.

Some desperate parents already falsify documents to get 14-year-olds into university. The next progression is normalized admission at 13, at 12, and more pressure to have children reading at three and testing into secondary school at eight.

Nigeria could create generations of high-achieving individuals who cannot maintain relationships, cannot manage stress and cannot parent their own children effectively because they never learned these skills themselves

Anticipate the emergence of acceleration as an education sub-industry.

Already, private schools advertise early graduation as a selling point.

Soon we’ll see specialized coaching for underage admission, consultancies that help parents game the system, a whole economy built on rushing children through childhood.

Look for the mental health crisis to worsen.

Nigeria already has inadequate psychological support infrastructure.

Add thousands of emotionally immature graduates to workplaces and universities, and the country will be drowning in anxiety, depression, and dysfunction with nowhere to treat it.

Children who skip emotional and social maturation don’t just struggle in their twenties; they carry those deficits through life.

Nigeria could create generations of high-achieving individuals who cannot maintain relationships, cannot manage stress and cannot parent their own children effectively because they never learned these skills themselves.

Nigeria risks an ultimate systemic collapse.

The more society normalises premature graduation, the more it erodes the foundation of healthy development.

That erosion doesn’t stay contained.

It seeps into workplaces where nobody can collaborate, into communities where adults still think like adolescents and into a nation that produces credentials without competence.

The issue cannot be addressed by an education policy alone.

Parents need to write a better policy for their children’s future.