Senior lecturer at the University of Lagos, Dr. Oyenike Adeosun, sheds light on issues affecting Nigeria education system and how the problems can be tackled:

In other climes research by universities drive technological, industrial and even medical development. Why is our case different?

It is true there is a disconnect between research in the Ivory Tower and national development. If anything, we import knowledge and consume products of other peoples’ knowledge.

Why is this so? So many hypotheses. It is not that Nigerian academics don’t sometimes engage in ground breaking research, but there are usually a number of encumbrances.

One, I’m not sure Nigeria as a country has a national research agenda.

Even though there is some policy in place about research driving national development, about the role of the higher education in impacting the community through research and so on, there is little to nil commitment to these policies on the part of the government.

Even the corporate organisations’ attitudes toward local researches and inventions are not encouraging. Most will rather fund Nollywood and entertainment projects than fund research.

Though we often read everywhere about availability of research funds, they are usually too small to conduct ground breaking research.

For instance, a number of colleagues are complaining about research funds from TETFund, either being too small, the bidding process usually cumbersome or the criteria for award usually not objective. We talk about grants from donor agencies – such usually have their own research agenda which may not agree with your area of expertise or even national needs.

Colleagues in other climes usually have research funds, which they can access at any time, and if they justifiably need more, they are given. In essence, they have support system that is lacking in our own context.

At the institutional level, no Nigerian university is known for a particular research focus or expertise. We award a potpourri of degrees without specialisation.

It is not that Nigerian academics don’t sometimes engage in ground breaking research, but there are usually a number of encumbrances

How can we make education at all levels more impactful?

There is the need for commitment at all levels, let’s go beyond paperwork and lip service. A Kenyan colleague was telling me Nigeria has good policies but bad implementation.

He confessed that they always seek out Nigeria’s documents on issues concerning especially education. In 2016, I met some officials at JAMB headquarters in Abuja who came to study our examination system.

So, let’s be committed to effective systems and processes. Let there be stronger synergy between government, school and corporate bodies.

And let companies get value for their money; that is the only way they can support education. Also, let’s take from best practices around the world.

Nigerians are well travelled and most studied abroad, even at graduate levels. What do we learn from all these places?

And while we are doing that, incorporate those with our local sustainable challenges, for though the world is a global village, our curriculum should also have local relevance.

Do you think strikes have been productive?

Maybe very minimally, and unless you look deeply, you may say none at all, although ASUU has remained one of the formidable unions in Nigeria.

But what does that translate to? Apart from slight increments in salaries and payments of stipends out of the backlog of emoluments and allowances, what have we achieved?

In 2005 when I joined the university, my salary was more than $1,000, now after almost 15 years, and in spite of so-called increments, my salary is lower than $1,000. Is that not retrogression?

Of what significance is my career advancement if my salary is increasing but my purchasing power is getting weaker? No wonder, we keep having brain drain!

But our agitation is beyond money. Since ASUU crept into my consciousness in 1999, focus has majorly been on revitalisation of public education, some level of university autonomy, adequate funding and quality infrastructure.

But these issues still remain the same after the 13th or 14th strike action of 2018.

In 2005 when I joined the university, my salary was more than $1,000, now after almost 15 years, and in spite of so-called increments, my salary is lower than $1,000

What do you think is the solution to strikes?

First, a listening, committed, focused government. Government that knows and does what is needed, right and expected without being forced to give it.

Government that is forward looking, and genuinely loves the masses. Government that understand the concept of democracy, and the rule of law and the close link between good education and quality living.

This commitment will enable them fully take care of basic and secondary education. Should it be free? Not necessarily!

Free education in our clime is a political agenda and cannot be qualitative. But it should be minimally affordable, functional and sustainable, and people should be supported with the wherewithal to be able to pay for it.

In this regard, privatization of basic and secondary education should be reduced to the barest minimum, and when few private schools are allowed to operate, they should be seriously regulated.

Do you think Nigerians should be prepared to pay for quality higher education?

University education is not basic education, and it is not meant for everyone. The struggle for university education is the outcome of failure of basic education and technical education.

If both are functional, and incorporate the necessary skills, we don’t all need university education. But we should first focus on quality and affordable (not necessarily free) education at the lower levels.

I attended free primary school and very-affordable fee paying secondary school in the eighties.

Though the content of the curriculum was not as deep and expanded as it is now, but the quality of learning experiences in terms of exposure to practical skills, field trips, play-learning, etc., put me in a very good stead to cope with more expanded curriculum later in life.

That is functional and quality education. Those enriching experiences are absent now, children just read, cram and pass examination.

So, if we are canvassing free education, quality should not be compromised. In fact, if we have to choose between the two, we should choose quality learning.

Free education has many components – the one I benefited from during Bola Ige administration in Oyo State came with free tuition and free offer of core textbooks.

Since ASUU crept into my consciousness in 1999, focus has majorly been on revitalization of public education, some level of university autonomy, adequate funding and quality infrastructure. But these issues still remain the same after the 13th or 14th strike action of 2018

Nigerians spend about $2bn on foreign education annually. Do you see this trend reversing soon and how?

Not at all, unless we are beginning to make drastic changes in the process and system of our education.

Even poor people are sending children abroad. I’ve seen middle class families selling their businesses and relocating outside the country just to have access to better education for their children.

People who remain in Nigerian schools stay with one leg in, and are continually looking out for a window of opportunity to get out.

It is not only a function of quality, even access is a problem. See how many hurdles candidates need to cross before getting admission to higher institutions.

International communities have seen that Nigeria is a vibrant market for their education, so they have agents and admission advisors all over the country.

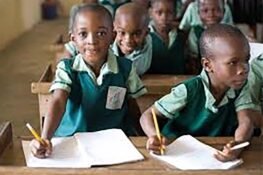

There are over 10.5 million out-of-school Nigerian children; what do you think we can do to remedy this?

Out-of-school children is a function of many factors. In fact, the Executive Secretary of UBEC puts the current figure at 13.2 million which I believe is still a conservative estimate.

In a country where we don’t even know our actual population figure, where significant number of births are not registered, how do you determine the actual number of school age children, and those that are not in school?

What about the ones you don’t have access to, in farm settlements and isolated villages?

So many factors are contributory: insecurity, insurgency and displacement, increasing poverty, illiteracy, ignorance and cultural/religious practices, ill-health, irrelevant, uninteresting and non-challenging learning leading to high incidence of drop-outs, etc.

So, there are different causes with varying magnitudes in different contexts and regions.

We need to examine each instance, what is causing this in this region, and put sustainable strategies in place to address the issues.

Note my emphasis on sustainable strategies, and the pluralised issues. One, in Nigeria, we usually develop programmes and create projects haphazardly, without putting measures in place to evaluate the effectiveness, and if found to be working.

We don’t look at how to sustain and maintain it continuously; so most of our projects are usually abandoned.

Out-of-school children has been in our dictionary since Obasanjo launched UBE in 2003, and after almost two decades, after being signatories to so many international treaties and conventions, despite so many pet projects, government initiatives, interventions by NGOs and international bodies, the number keeps accelerating significantly!

What is the problem? Too many discrete programmes with no integrated management, no cause-specific intervention and no attempt at feedback, redefinition and sustainability as may be required!

Privatisation of basic and secondary education should be reduced to the barest minimum, and when few private schools are allowed to operate, they should be seriously regulated

Rev. Father Hassan Kukah offered to train 10 million almajiri children in the north and it generated so much controversies. MURIC says it’s a plot to convert Muslim children to Christians. Is there anything wrong with Kukah’s proposed intervention?

Without sentiments, Rev. Kukah’s offer is very laudable and should be appreciated by everyone concerned with the plight of these children.

Many of our parents, some of whom are Muslims had at younger ages benefited from Christian education and they are still able to retain their faiths.

However, as I said earlier, there is need for coordinated and integrated efforts. If MURIC is against Kukah’s proposal, what alternative do they offer?

Almajiri schools have been launched and left in the hands of Muslims to administer, what did they bring out of it?

Part of Nigeria’s problems is seeing everything with religious bias. MURIC itself admitted Almajiri system is a social menace, so why kick against a sincere offer at remediation?

These children are victims of some economic and social slavery but coloured by religious beliefs.

It is not a Northern nor Islamic problem, but Nigeria’s problem as we are all experiencing the repercussion, so proposing it should be solved by northern Muslims translates to having a narrow perception of the problem.

Go to major cities in Nigeria and you will see youths produced by the system maturing into miscreants, renegades, drug addicts, rapists, etc. and especially tools in the hands of insurgents.

If MURIC is against Kukah’s proposal, what alternative do they offer? Almajiri schools have been launched and left in the hands of Muslims to administer, what did they bring out of it?

Do you see any modifications to the Kukah’s proposal?

While his proposal is remedial, we should first applaud him and cooperate with him to ensure its success.

And there are other individuals, agencies and NGOs who have been working to rehabilitate these children but with little success because the challenges are awesome.

All the discrete projects and singular interventions must be brought together for proper coordination and sustainability.

We must put sentiments aside and be sincerely committed to solving the problem, including digging into the root causes.

Why would parents willingly abandon their children to some unknown people, destination and fate? Ignorance, overpopulation, poverty, illiteracy, warped belief or value system, lack of empowerment, coercion, religious deceit, political subjugation and exclusion, gender inequality, social and cultural expectations, large family, polygamy?

These issues are interwoven and co-dependent and should be collectively and comprehensively addressed with strong leadership by government.

We should not also jettison the efforts of past governments; for instance, how far with Almajiri model schools launched in 2015. What are the gains and how do we sustain the gains, if any? What are the weaknesses?

How do we strengthen them?

Out-of-school children has been in our dictionary since Obasanjo launched UBE in 2003, and after almost two decades, after being signatories to so many international treaties and conventions, despite so many pet projects, government initiatives, interventions by NGOs and international bodies, the number keeps accelerating significantly!

Where do you see public universities in Nigeria?

The vision is a bit blurred for now. It is commonly said we still have a long way to go and I quite agree.

How long, I don’t know but the longest journey starts with just a step. In terms of taking steps, let me appreciate the efforts of our universities’ management teams.

I am an insider and I know quite a lot are been done internally. But we need strong systems and support, especially in terms of political governance.

I have talked about studying and adapting workable models. I have talked about professional commitment.

I mentioned theory-practice nexus; strong, continuous and sustainable collaboration between the industry, government agencies and the academia.

I think with new and renewed focus, necessary resources, strong institutional management through quality leadership and followership, strategic planning and continuous systemic assessment, focus on creativity, technology- and development-driven learning, we should make significant progress and impact.