Even though the attention of the world was focused on the role of the media in elections and democracy on the World Press Freedom Day, the shadow of last year’s murderous attacks on free speech still loomed large.

Will this be the new normal?

In July, The Economist, quoting a report by Freedom House, described 2018 as the year when the muzzling of journalists and independent news media was at its worst point in 13 years.

And that was before the Philippines’ reprobate President, Rodrigo Roa Duterte, slammed frivolous and repressive charges of tax fraud and cyber libel on journalist Maria Ressa, an outrage only preceded in scale and ruthlessness by the state-sponsored butchering of Jamal Ahmad Khashoggi inside the Saudi Embassy in Turkey.

Somehow, in that grim year, Nigeria also moved up three places on the Freedom House ranking index.

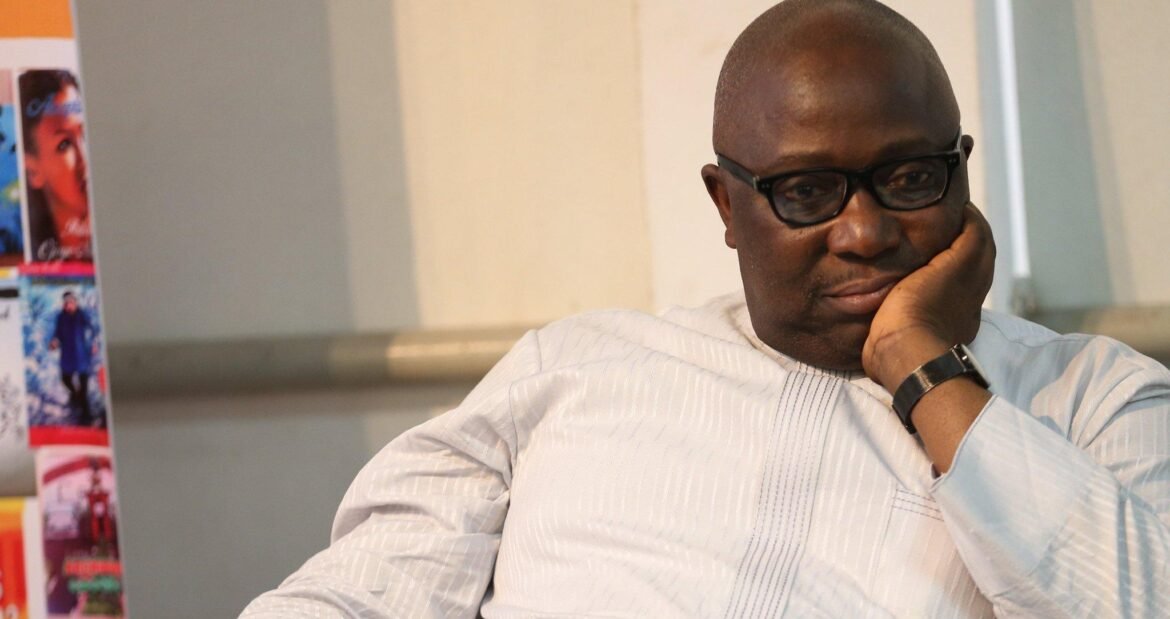

In light of what we know about the odyssey of press freedom last year, however, the Editor-In-Chief of Premium Times, Dapo Olorunyomi, whose online newspaper is a relentless thorn in government’s side, must be asking himself if much has changed since the 1990s when state-sponsored terror against the press forced him into exile.

The military may be gone, replaced by politicians in civilian dress, just as surely as decrees have been replaced by a constitution with elegant provisions for press freedom, but old habits die hard.

In a country where the police still use outdated sedition law against the press; where the state oil corporation insists that it is outside the reach of the Freedom of Information law; and where the army raided a newspaper house last year and trashed its computers, journalism that makes powerful state officials uncomfortable could carry a heavy prize

That’s why the Nigerian military authorities descended on Olorunyomi two years ago. They did not quarrel with the facts reported by Premium Times that the Chief of Army Staff, Lt. General Yusuf Buratai, had bought houses in Dubai beyond his means.

Their grudge, a hangover from the military era, was the fact that the newspaper had the temerity to expose the acquisition, without a thought for the potential “national security implications.”

In retrospect, it may sound like a laughing matter. But it’s not.

In a country where the police still use outdated sedition law against the press; where the state oil corporation insists that it is outside the reach of the Freedom of Information law; and where the army raided a newspaper house last year and trashed its computers, journalism that makes powerful state officials uncomfortable could carry a heavy prize.

Yet, this is precisely the type of journalism that Olorunyomi has dedicated over 30 years of his life pursuing: journalism of consequence.

An alumnus of the Kwara-based Herald, he later moved to Lagos where he joined African Concord magazine. One of his major cover stories, entitled, “Has Babangida Given Up?”, was a damning story of the military president in hostage.

That story led to the closure of Concord Press by the Babangida regime, after the Editor-In-Chief, Bayo Onanuga, refused to apologise to the military authorities in spite of the publisher’s advice.

By the time Olorunyomi arrived at The News (after a stint at the African Guardian), with Onanuga, Kunle Ajibade, Babafemi Ojudu, Seye Kehinde, and Idowu Obasa, his talent for roaming dangerous territory was advanced and famous.

Onanuga told me that Olorunyomi “is a journalist with a huge appetite for risk, wholly invested in pursuing truth and helping younger journalists imbibe the same culture.”

He continued: “Often looking like an almajiri, Dapo spent himself broke looking out for others’ professional wellbeing.”

That virtue appears to be in short supply. The awareness of consequential journalism whether on elections or immigration, is disappearing; never mind the willingness to pursue it.

The awareness of consequential journalism whether on elections or immigration, is disappearing; never mind the willingness to pursue it

Across Africa, at least 14 countries will hold major elections this year.

A few, including Nigeria, South Africa, Senegal and Guinea Bissau already have. Will these elections be free, fair and credible? Will they reflect the genuine choice of citizens about who they wish to govern them? Will the press provide fair, balanced coverage and inspire enlightened choices?

If the media hopes to play any consequential role in these elections, it must first examine itself.

It’s a fact that threats to press freedom from state and non-state actors are rising, and therefore, collective global action by citizens, institutions and responsible governments must continue.

There is a proliferation of the multiple-hat journalist: the journalist-politician; the journalist-entrepreneur; the journalist-consultant; and the journalist-agency. It’s an egregious form of specialisation, which takes care of everything, except what it should really be taking care of: journalism

But if Olorunyomi’s career tells us anything, it is that even though outside threats have become somewhat malignant over the years, they are not new. Journalism must examine itself to play any credible role in elections and to deepen democracy.

A few of the deadly worms eating the profession are inside; they must first be purged.

There is a proliferation of the multiple-hat journalist: the journalist-politician; the journalist-entrepreneur; the journalist-consultant; and the journalist-agency.

It’s an egregious form of specialisation, which takes care of everything, except what it should really be taking care of: journalism.

The consequence is that professional boundaries have become so blurred that they are, in fact, almost non-existent.

If there was a time when facts were sacred and comments free, the transactional genius of many newsrooms have now merged facts, comments and “factcom” into a single commodity, shortchanging press freedom and damaging ethics.

Credibility is a casualty most times, but especially so during elections.

This is not helped by the shoestring budget of many newsrooms and proprietorial pressure on editors by media owners who treat their organisations like the media arm of their political party or tribal newsletters.

Pandering to big business, to cushion the effect of poor funding, has also weakened the capacity of the media to play an effective role in deepening the democratic process, while fake news, fake websites and marketing remain a clear and present danger.

In “Can you trust the media?”, a book that mocks the mainstream media’s claim to the custodianship of public trust, Andrian Monck, said, “I believe that instead of asking whether media can be trusted, we need to teach people to live in a world where trust is something that is withheld.

“People need to be skeptical as a matter of course. Then, they won’t be disappointed. Skepticism is the faculty to which they should be appealing, but instead the media is tying itself in knots over credibility and trust.”

That’s fine. But we cannot throw up our hands or be rooted in a spot until our feet is overgrown with the weed of self-doubt.

Pandering to big business, to cushion the effect of poor funding, has also weakened the capacity of the media to play an effective role in deepening the democratic process, while fake news, fake websites and marketing remain a clear and present danger

A day like this not only serves to remind us of the work that needs to be done, it also points us to icons like Olorunyomi who, in spite of the odds, remains a shining example.

We have seen from Premium Times, for example, how it is possible to tackle resource limitation by collaboration.

Think of the collabo between the newspaper and the international consortium of journalists that produced the Pulitzer-winning Panama Papers. Can we have more of that?

Change may sometimes be slow in coming, like the case of former Communications Minister, Adebayo Shittu, still twisting in the wind by a shameful thread, months after he was exposed for dodging national service and lying about his NYSC certificate.

Press freedom is not given. Nor does it make sense to mark it once every 365 days. It is freedom that is earned daily and every deadline minute, through toil, diligence and refusal to settle for mediocrity in the search for truth

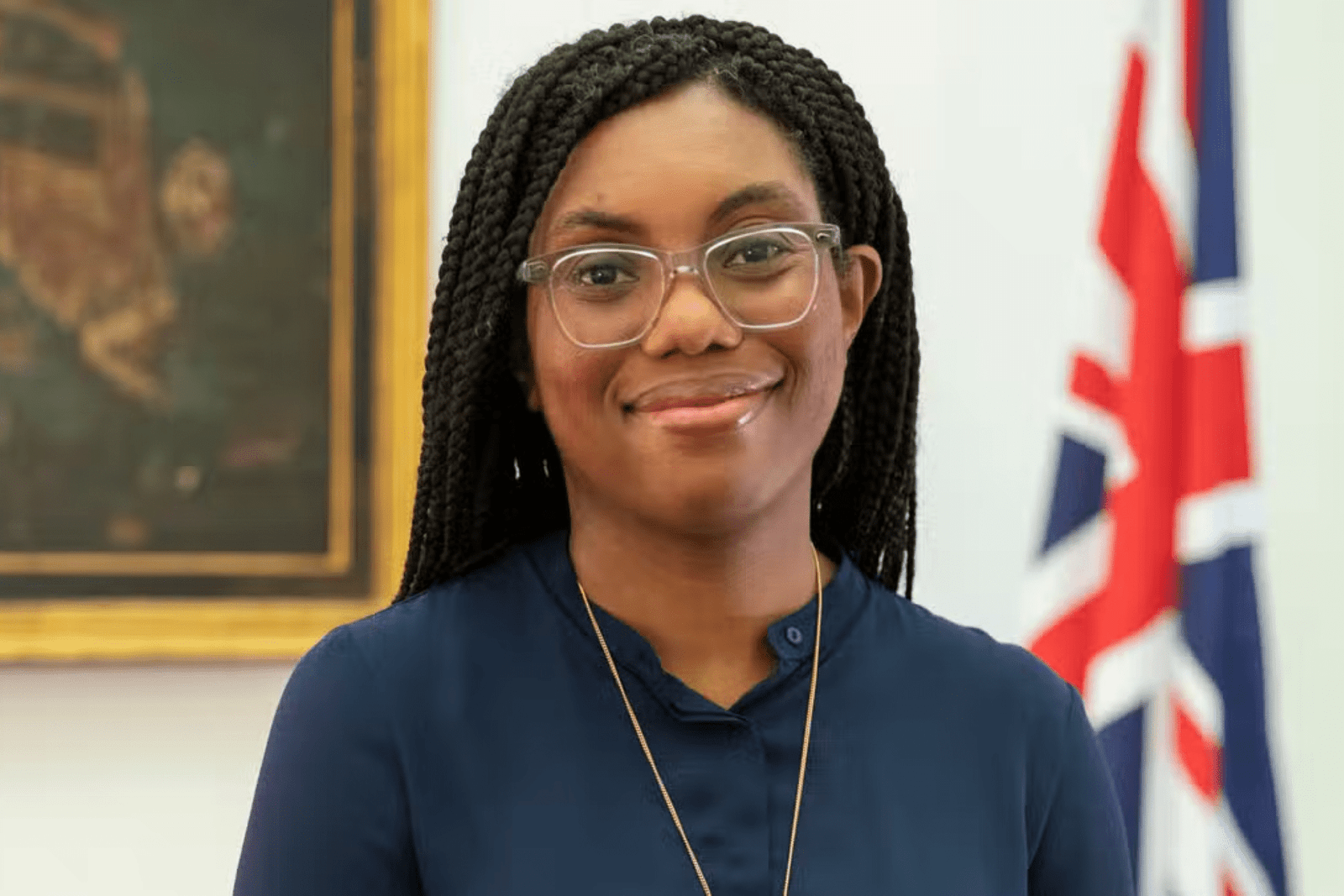

But we have also seen that if journalism persists long enough, it may lead to inevitable tremors – the removal of former Finance Minister, Kemi Adeosun, and presidential pension task force chairman, Abdulrasheed Maina, being two examples.

As Dapo Olorunyomi leads Premium Times in the newspaper’s struggle to become a sustainable business model, without which it may become increasingly vulnerable to predatory interests – or predatory poverty – it would also be interesting to see what other media houses may learn from its current funding mix of advertising, crowdfunding, and perhaps monetisation of differentiated content.

Press freedom is not given. Nor does it make sense to mark it once every 365 days. It is freedom that is earned daily and every deadline minute, through toil, diligence and refusal to settle for mediocrity in the search for truth.

There are examples to inspire us, if we care to look and see. Olorunyomi is one.