Rather than provide answers to why they were the true winners of the 2019 presidential elections, the petition submitted by the People’s Democratic Party to the election tribunal appears to raise even more questions about the party’s claims to victory.

For a presidential petition covering the elections in 119,973 polling units in across 36 states, with an average of 29 million citizens voting, the document cataloguing all of PDP’s grievances on how the elections held is unusually brief.

All of the issues raised in the petition are typical of every election that has been held in Nigeria over the last two decades. They include allegations of militarisation of the voting process, intimidation of voters and violence.

Added to that are allegations of a large number of cancelled votes, over-voting and purported denial of access to the ballot in various states.

But central to the party’s case at the tribunal is what it says is the true result of the presidential elections gotten, stolen, retrieved or hacked from the server of Independent National Electoral Commission.

There is also the allegation that the results from the server are filled with errors and figures that don’t add up, and suggest no candidate apart from the two leading ones could get a single vote. This is highly unlikely in an election where even a state governor raised concerns about how confusing the ballot paper was.

Reading through the petition creates the impression it was written more for media and public consumption rather that a legal document crafted to convince the tribunal why the law is on their side

The inconsistencies actually do more damage to PDP’s case.

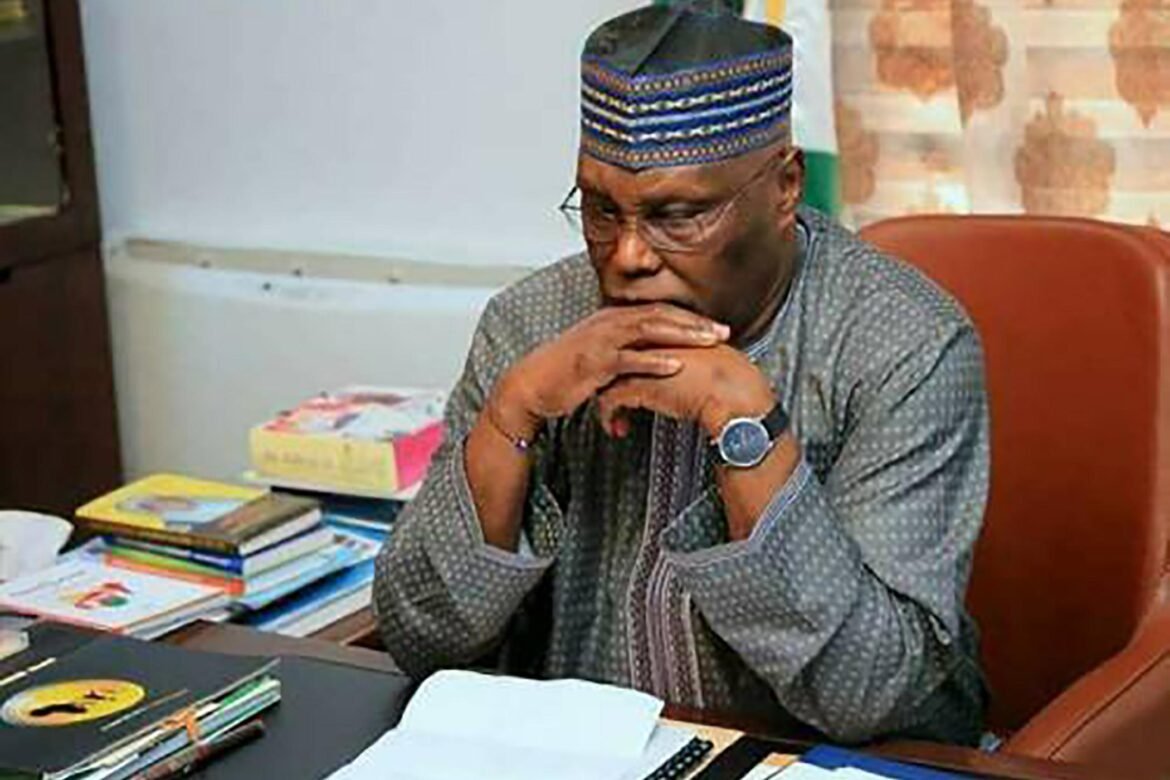

In spite of the long list of Senior Advocates of Nigeria charged to litigate the election petition of the PDP and its presidential candidate, Atiku Abubakar, what was submitted to the tribunal appears to have fallen short.

Reading through the petition creates the impression it was written more for media and public consumption rather that a legal document crafted to convince the tribunal why the law is on their side.

First is the fact that the entire case is hinged on the results fed into the server of the Independent Electoral Commission and the opposition party plans to build its case around this.

The only problem is that even if the results are genuine, how will the PDP explain how it came about it and should the party have relied on “stolen” data in its petition?

The second issue is whether it even matters. How will the tribunal respond when two conflicting results are presented to it, one generated and transmitted manually and the transmitted electronically, which should explain how it found its way to the server.

Which of the two results is recognised by law and which will the tribunal accept as authentic?

For a presidential petition covering the elections in 119,973 polling units in across 36 states, with an average of 29 million citizens voting, the document cataloguing all of PDP’s grievances on how the elections held is unusually brief

Before the elections, there was uncertainty about which electoral law would be used in the conduct of the elections. The sticky point was how election results would be transmitted, either manually of electronically.

INEC has consistently said it was ready for the elections regardless of whichever law was approved to by the executive and legislative arms of government.

In the end though, President Muhammadu Buhari withheld assent the 2019 electoral bill forcing the commission to conduct the elections with the old law which only recognises the manual recording, transmission and collation of election results.

But since INEC had said it was ready for and could do both the manual and electronic transmission of results, is that what the commission did as PDP is alleging?

Did INEC log in one set of electronically transmitted results on its server and declare a different set that were transmitted and collated manually?

And based on the petition submitted by the PDP, the results from Rivers were missing. Even if elections were not held in one or two local governments in the state, should the rest of the presidential election results be on the server since they are transmitted directly from polling units?

The Atiku campaign has identified a whistleblower website, factsdontlieng.com as the source of this data alleged to be the genuine results of the presidential elections held on February 23, 2019.

It would be irresponsible for the campaign team, the party and its lawyers not authenticate this information before using it in a petition presented to the tribunal and also planning to tender it as evidence.

There is also the allegation that the results from the server are filled with errors and figures that don’t add up, and suggest no candidate apart from the two leading ones could get a single vote

It must therefore be assumed that the PDP has verified that the results it is relying on in the petition were not fabricated and that the party can also vouch for the credibility of the website.

From all indications, the website didn’t exist before suggesting it was set particularly and a not for the purpose of hosting the results.

That in itself also raises questions on whether someone on campaign team has links to the site or was responsible for setting it up.

It is improbable that the information from the server were legally obtained. The question however is how stolen documents can be verified? Was the server hacked?

Even if it was gotten from an insider in INEC, who ordered the theft and was it paid for?

All of these questions suggest that the PDP has already tainted its case at the tribunal unless INEC officially and freely handed the information to the PDP legal team, in which case there should be no doubt about the authenticity of the results the commission has recorded on its server.

What it casts doubt on will now be the official results declared by INEC and the victory of President Muhammadu Buhari.

But maybe the most fundamental issue for the PDP and its petition is whether the results from the server carry any legal weight as against the manual results, which are all that are recognised by the 2010 Electoral Act

Naturally the PDP had thousands of agents on ground on Election Day. So it is safe to say the party had more eyes on the ground than the media and observers put together.

Still it would close to impossible for the party to fully document all that transpired in all the 119,000 polling units. Even INEC had to rely on several institutions and particularly the NYSC to man all the polling units.

And from what was witnessed by the media and observers on election duty, there was a relative low turnout of voters on Election Day and this reflected in the results showing close two million fewer voters than recorded in the 2015 presidential elections.

The results presented by the PDP petition and allegedly retrieved from INEC’s however show otherwise. It instead shows roughly five to six million more voters than those that participated in the 2015 elections.

The obvious conclusion is that the media, local and international observers were wrong in their assessment that there was a low voter turnout during the elections.

But maybe the most fundamental issue for the PDP and its petition is whether the results from the server carry any legal weight as against the manual results, which are all that are recognised by the 2010 Electoral Act.

It is especially important since the PDP is trying prove that there was a substantial breach in the electoral law to warrant the declaration of President Buhari as the winner of the elections null and void.

It doesn’t need mentioning that the results from the server do not meet any criteria set by the law guiding the elections.

In that sense, the real mystery isn’t whether the server, as alleged by PDP exist and contains that information, but why Atiku and his party will choose to build their entire case on evidence that isn’t necessarily admissible in court or at the very least, does not carry the weight of law.

On the other hand, the result sheets showing President Buhari won the elections, even if they weren’t genuine, were duly signed and declared by a returning officer at various levels as required by law.