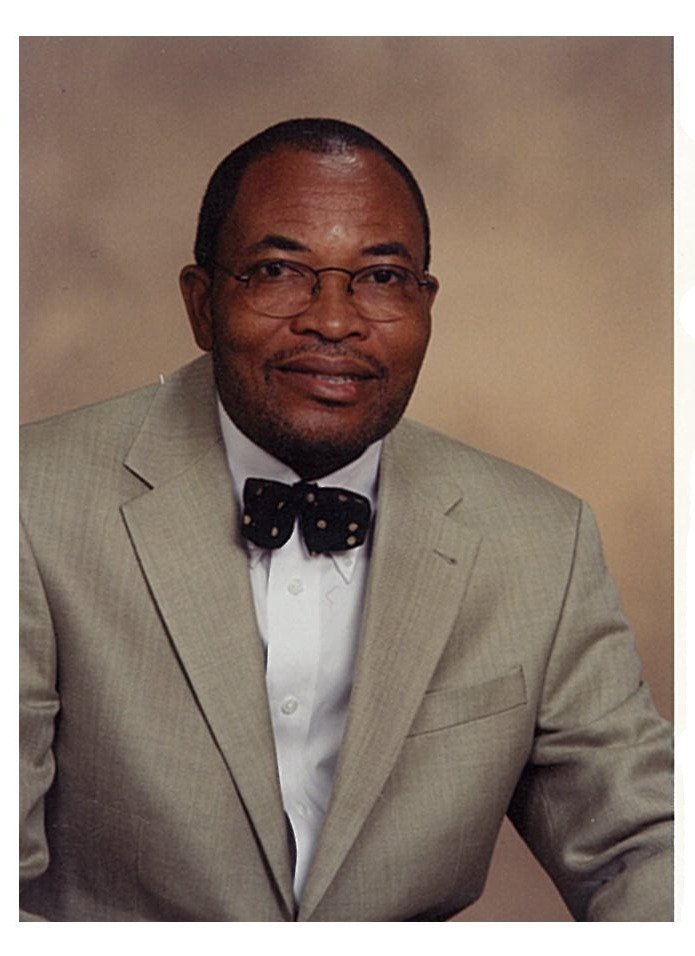

Prince Gbadebo Adeyeye, a US-based Public relations expert, is the proprietor of Crown Heights College, Ibadan, a school patterned after the US education system. In this chat, he tells The Interview his vision for the school. He also proffers solutions to the various challenges besetting Nigeria’s education sector, among others.

What was on your mind when you left your lucrative public relations job in the United States to establish an American-style and standard secondary school at Ibadan Nigeria in 1997?

First of all, there are many people in the world who have great dreams, and we admire them, marvel at their persistence and determination to pursue those dreams. There are others, however, who have dreams so profound that we are not content to simply watch. We just want to be part of that dream. We want to help them to achieve their dreams and live within it. And in the rarest of cases, some very special people convince us that their dream is more real and vital than anything that we have ever touched or experienced. The story of Crown Heights College is about such real dream. Let me say that in my journey of life, I have reached a point where, apart from my family members, what I care about is doing whatever I can to make sure that people around me, particularly the younger ones, are not denied the opportunity to discover their potential educationally and socially no matter what it takes from me. And this was just my dream when I started Crown Heights College in 1997.

What’s your fascination with education?

Unless we just don’t want be honest, there is no better way to contribute to the development of Nigeria than investing in the citizens’ education, particularly at that time when our education system was poisoned by those enemies of school children in the military. That is why I thank God today that I am part of the solution. Money is not everything. I always feel invigorated by working with children, especially each time I have the opportunity of teaching them business studies or economics in the classroom.

As a proprietor of ‘American standard and style’ secondary school in Nigeria, what were some of the teething issues you faced at the beginning and how did you overcome them?

Truly, in the beginning, I had no idea of the sacrifices it would entail for me, particularly in a society where everybody is a ‘deacon’ or ‘deaconess’ yet very anti-entrepreneur; from the local government workers to contractors and even some employees who are not ready to give their services other than just to reap from the employer. And because of the unfriendly nature of our society to business, I have asked myself many times, ‘Will I ever be anything again other than the proprietor of a small private school in Ibadan?’ Of course, those who know me very well know that I am very maniacal when it comes to my work. But I thank God today for His compassionate treatment to me despite the environmental discouragement.

Many believe that most private school proprietors are in it just for the money; how can the regulatory agencies ensure quality?

In a disorganized society like ours, unfortunately, discussions about quality control are very difficult. For example, how are we going to convince the Ministry of Education or NECO officials, who drive around the cities daily, that such practice as collecting fringe benefits from unaccredited private school proprietors is dangerous to our education system? I believe we need to sterilize the Ministry of Education first.

From your experience, having been in US, what are those things you think Nigeria could learn from its educational system?

Let me say this for the record. I have spent many years of my life expressing my opinions on different national issues, and I will be lying if I say that I am not worried about the future of our country. The point is that I am no longer worried about Boko Haram because I know that, very soon, the Lord will conquer their empire. But what I am really worried about is the business-as-usual attitude that exists in our society, particularly in the university system. First, I have been living in America for 36 years. In those 36 years, for example, not for one day did I see a whole university campus shut down by employees, (academic or non-academic) for any reason. Secondly, as of today, the City University of New York has produced alumni winners of 12 Nobel prices in different academic disciplines, namely: Kenneth Arrow, Economics, class of 1940; Robert Aumann, economics, class of 1950; Julius Axelrod, medicine, class of 1933; Stanley Cohen, medicine, class of 1943;Gertrude Elion, medicine, class of 1937; Herbert Hauptman, chemistry, class of 1937; Robert Hofstadter, physics, class of 1935; Jerome Karle, chemistry, class of 1937; Arthur Kornberg, medicine, class of 1937; Leon Lederman, physics, class of 1943; Arno Penzias, physics, class of 1954, and last but not the least, Rosalyn Yalow, medicine, class of 1941. In 2013 alone, the students of the same City University of New York, including a young Nigerian girl, Deborah Ayeni, won a record 16 National Science Foundation scholarship awards of $126,000 each for graduate study in the sciences. Again, this is only the City University of New York, not to talk of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, or Columbia, e.t.c. Back in Nigeria, while some of our professors, including those from the so-called first generation universities and the best (of our brains) travel to Europe and America every year, chasing not knowledge but hard currency, the majority of those at home are happy barricading the university gates across the country over the non-payment of their bonuses and leaving their students in the streets of our cities operating ‘okada’ (commercial motorcycle) business. This intellectual terrorism is very cancerous to our education system and to the whole economy, especially in a country where the president takes flight to the United Kingdom every three months for medical treatment! Agreed that, for many years now, the Nigerian government has failed its citizens in its constitutional duties, both at home and abroad; nevertheless, the voodoo professors in our universities must understand that there is a moral difference between the use of force to dialogue and the use of force to be rewarded; otherwise, their Oshiomhole tactics will continue to destroy our university system in the 21st century the same way the manufacturing sector was annihilated!

In your article, ‘Agony of Education Imbalance in Nigeria,’ you lamented the out-of-balance school curriculum and overloading of pupils with over 15 subjects; what do you think are the best alternatives to this?

Again, let me say that the cop-out of blaming students’ failure on poverty in Nigeria is morally and intellectually vacuous! For example, when I was growing up in Ekiti more than five decades ago, there was more poverty but far less failure in our schools. The difference was that all schools in Ekitiland enforced standards, and were properly monitored by education officials from the ministry before corruption was introduced into the civil service. Secondly, before the Nigerian education system was poisoned by members of the Supreme Military Council in the early 80s, we must remember that schools were established to deliver good education to students. And many people will agree that the primary goal of public schools is to teach students how to read and write. Unfortunately, whether by accident or design today, public schools in Nigeria have been rendered unproductive because of the burden placed on them and their helpless students a majority of whom are taking more than 18 subjects in junior school, including Arabic Language that they cannot speak, or write. But what our leaders don’t understand is that failure is a pervasive social disease. When the school fails, teachers fail and their students fail as well. When that failure is repeated, it erodes the confidence of both students and their teachers. Students may be left with a sense of failure and diminished self-worth that may affect them for the remainder of their lives. In addition, teachers who do not advance through the system, and who do not experience the required success with their students may leave education for a less frustrating career. And for such cycle of failure to be broken in our society, our leaders must develop and nurture success. They must turn away from treating education matters with religious and political interest. They must note that there is no substitution for the pleasure of success. That is why the original wisdom of our founders is urgently needed in Nigerian education sector.

What are the three things the government can do to change the fortunes of education in the country?

Former American president James Madison said, ‘A people who mean to be their own government must arm themselves with power that knowledge gives, and any popular government without information or the means of acquiring it must be a prologue to a farce or tragedy, or perhaps both!’ Agreed, political leaders who are truly exceptional like Chief Obafemi Awolowo come rarely. In the old Western Region, for example, some of the most effective educational policies of Chief Awolowo happened not as a result of political pressure, but as a result of dialogue between the political and educational leaders. Unlike the present group of arrogant politicians in the country today a majority of whom are not well informed, Awolowo spent his entire political career representing something as important now as it was important during his lifetime – an uncompromising pursuit of educational excellence that shows the entire Western Region at its best in our country. And to curb the present decay in Nigerian schools, first, I believe that a total restructuring of the nation’s education system is needed, with the encroachment of the federal government since 1979 into what had been mission schools, and the state government decisions be removed immediately. Second, all corrupt officials in the Federal Ministry of Education be flushed out without delay; and third, the uninformed politicians in all education policy making committees be sent back home with their ludicrous contributions.

How best would such policies be implemented?

The best way for any government policy to be implemented in any society, especially a disorganized country like ours, is by having the courage to make tough decisions.

Many stakeholders have continued to lament that the Nigerian graduates are not employable. What ways can we deal with this problem?

To stop graduating functional illiterates in our universities, again we must raise academic standards to dispel the destructive myth that all Nigerian young men and women must have university degrees. In addition, government must develop alternate career tracks based on modern-day apprenticeship rather than the emphasis on classroom learning. We must realize that, today, too many students unsuited and uninterested in the university waste four to six years that could have been better spent gaining practical workplace experience. Encouraging every citizen to have a university degree might sound appealing in the abstract, but for many young people in Nigeria today, technical or practical workplace skills would be more appealing, more useful, and more appropriate. After all, a good plumber is a lot more useful for the society today than a badly trained lawyer from any of our chaotic universities.

Nigeria has about 10.5 million out-of-school children, one of the highest in the world; what strategies would you suggest to government and other stakeholders in the education sector to get out-of-school kids back to school?

One of the most inspiring stories of the past 50 years has been that of developing countries that were mired in absolute poverty after the Second World War but adopted the right economic and educational policies that triggered astonishing prosperity in their nations. Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Chile have succeeded because they simply stressed basic economic principles, such as lower government expenditure, open market, lower importation taxes, competitive industries, and, more importantly, they placed a high premium on citizen education. But in our own country, one thing is certain: we cannot move from poverty to progress in Nigeria unless we project values that go beyond corruption, private jets and Dubai mansions. And how we meet these serious challenges in the 21st century will determine not only our future, but the future of our children and grandchildren, particularly their education.

What is your opinion of the two years of the Buhari-led government? Are things changing in Nigeria and the Nigerian educational sector?

Many Nigerian citizens, especially members of the opposition, may not want to admit this, but unlike the previous administration, Buhari has been a good president in his first two years on the job. Infuriating at times, and very sleepy at others, but, overall, the former green-beret-dictator-turned-democrat is above average.

In general terms, has the present government delivered the change many Nigerians yearned and voted for?

Generally, President Buhari is doing well on his campaign promises. In fighting corruption, which is the most dangerous enemy of our nation, Buhari deserves a B+. It is clear that the president understands that most Nigerians want him to keep corruption in check. Also like the war against corruption, figuring out where to place millions of unemployed youth in the economy is one of those existential questions that we simply have to solve. I think Buhari deserves a C+ for his focus on the urgent need to provide employment for our youth.

Do you think the Nigerian government is doing enough for the Diaspora community?

First of all, any country that cannot protect its citizens at home and abroad is a failure in the comity of nations. Unfortunately, Nigeria has been in this category for more than 30 years now, especially when hundreds of innocent young men and women who travelled out of the country on different government scholarships were stranded in American cities as a result of failed promises by our so-called leaders.

Looking back, have you, at any point, felt you shouldn’t have left your lucrative public relations job in the United States to establish a school in Nigeria?

I have no regret at all. As I said, I will continue doing whatever I can to make sure that our younger ones are not denied the opportunity to discover their potentialities.

Do you have plans to go into politics in the future?

To be successful in Nigerian politics, one must have the anointing to steal, to kill and to destroy! Fortunately, I am too far from that anointing and that is why I can’t go into politics.

You will celebrate your 60th birthday in a few days; how would you describe your life so far?

Looking back at the past 60 years of my life, all I can say is thank God for His compassionate treatment to me. Of course, the journey has not been a smooth ride, especially after my mother’s death when I was only six years. But God has been faithful. What an amazing thing to know that He comes in so strong and so mighty when we are at our weakest points! I also appreciate everyone who has contributed positively to my life during the past 60 years – teachers who epitomized the true meaning of the profession, schoolmates, professional colleagues, friends and family members who have been very passionate, patient, respectful and kind to me.

What are those things you wish you had done differently?

Avoid trusting people at first sight, especially in a country where not every man in a suit and tie is normal.

What are the things that keep you awake at night?

Reading, writing and, above all, talking to God. Thanks to Amoye Grammar School, Ikere-Ekiti, for that training!