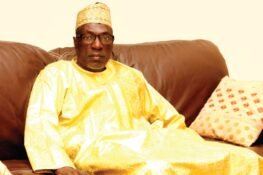

A journalist and writer, Segun Adeniyi was spokesman to President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua’s short-lived administration. He speaks to The Interview about his place in the saga of his principal’s health at the time, his exit strategy and his view about Jonathan and Buhari.

You served in the Presidency under a PDP government. Do you feel any kind of affinity towards the party?

No. I was picked from the newsroom. I was not a politician. I was a journalist. It just happened that the man I worked for was a PDP man. I never saw myself as a PDP man. It was not that I had anything against PDP. I didn’t feel inclined to join politics and I made that very clear. Of course, there were people in government who didn’t like it because I used to say it. It worked against me once. I remember the President was going for a meeting that I really wanted to be in because I knew some decisions would be taken there. But when he saw me, he said, ‘Segun you can’t go with me. You have always said that you are not a member of my party.’ And he didn’t allow me to go. Normally, we, the aides, go to the meetings. The point really is that I wasn’t a politician and I was not in any political party. I was an active journalist before I was picked, so at what point did I join a political party? I believe that political parties are organizations you join consciously, not something to which you could be adopted.

A lot has changed since you left government some seven years ago. In a way, the PDP became a victim of its own creation: the zoning of political power among the regions of the country; it proved to be too contentious. Was the 2015 crash of the party inevitable? And could you have predicted it considering the debate in 2011?

Yes. It is actually the first chapter in my book, 2011 and The Hard Bargain. It is very exhaustive because I spoke to all the principal characters at the period and they told me what happened with the zoning. Dr. Jonathan became president in May 2010 following the death of President Yar’Adua. There were negotiations before he was allowed to contest in 2011. It’s a complex and long debate. I believe that what happened in 2011 affected the 2015 election because there were issues that were raised then. There were promises that were made. There were negotiations that were agreed upon. Some of those issues and the way they played out affected the 2015 election.

Do you think the country needs to come up with new ideas to address issues like zoning considering the competition for power among the different regions?

There is nothing wrong with zoning. Every region, every zone in Nigeria can produce a president in terms of the human capital that we have. So, whether the presidency is zoned to the north, to the south, the east or the west, there are competent people everywhere.

Aside competence, what about competition? Was it not competition that brought zoning and also killed it?

No. It was not the competition that brought zoning. It was brought as a result of some feeling of marginalization. I remember in 1999, there was this notion that the presidency had been in the north for a long time. That was the basis for zoning. Of course, zoning was not a national thing; it was a party thing within the PDP and the military played into it. I covered the All Peoples Party (APP) primaries in 1999 and it was a joke. We went to Kaduna. They were moving from one place to another for three days. There were no primaries. All of a sudden they just announced that Dr Ogbonnaya Onu had become the candidate of APP. I left for Lagos and by the time I got to Lagos they said Chief Olu Falae had become the APP candidate. How? Olu Falae was the Alliance for Democracy (AD) candidate. They said there was a merger. All the scenes were manipulated by the military to ensure that a Yoruba man became the president in 1999. That was the basis of all those things. That is why, at the end of the day, we had two Yoruba men contesting against each other and it was the result of the injustice felt because of June 12. But PDP decided they were going to institutionalize it. The presidency was going to be zoned between the north and south, but it was just an arrangement by one political party. If another party had won in 2003; for instance, if Buhari had won on the platform of APP in 2003, it would have disrupted the whole calculation. So, zoning within the context of Nigerian politics as of today is a PDP arrangement.

Today, a lot of the anxiety generated by President Muhammadu Buhari’s health status is shaped by what the country went through with Umaru Yar’Adua. One thing that appears to be a constant is the secrecy surrounding the President’s health. Do you think Buhari should be more open about his health?

I don’t know what you mean by being open. The man went on leave and he said he was going do his medicals. He declared it and properly handed over. Part of the challenge in our case was that my late boss was not allowed to fully implement the constitution. If he had handed over to Dr. Jonathan, there wouldn’t have been an issue. In all the times that President Buhari has travelled, he followed the law: he handed over to the vice president. Now, as to the nature of his sickness, I can’t speculate when I don’t know. Also, the law does not require anybody to be compelled to reveal his health status. If you look at the Freedom of Information Act, it is actually on the issue of health that you cannot compel somebody to make a public declaration.

You have written about your experience in the Yar’Adua presidency and how everyone around the president responded to his health issues. According to your account, things took a turn for the worse in late 2009. Was there ever a point you felt it would have been in the nation’s best interest for the president to resign?

You know those kinds of things are personal choices. I didn’t know about his health until I got to the Villa and I took the appointment. The health challenge started very early in the administration. The choice was his to make: ‘Can I continue under this kind of circumstance?’ If he were alive, there are things I could have said. I hesitate to pass judgement on somebody that is already dead. So it is a tricky one for me. Given the nature of his health, I honestly don’t think Yar’Adua should have contested in the first place. But as to whether he should have resigned, it is a judgement call I can’t make for him.

Those were trying times and you were the face of the presidency. Will you forever be defined by the Yar’Adua episode?

How? I was his spokesman. For me, it was just a phase in my life. What the thing ensured was that, at every point, I was mindful that I had a life after the Villa. That is why I challenge people when they say ‘you are lying’. I never lied. I spoke five times when Yar’Adua was hospitalized and I recorded everything. Google is there. Anybody can Google me. I never lied about his health. In instances when I had nothing to say, I just kept quiet. I did that a lot. I was his spokesman, he trusted me. I couldn’t go out there and disrobe him. I also could not go out there and lie during that trying period as it were.

Your book offered glimpses of someone conflicted about where his loyalties should lie. With your long held exit plan, it was like you had one foot in and the other out the door.

I was loyal to Yar’Adua to the end. At a point, I realized I could no longer stay in government, but I told myself I was not going to say anything; I was not going to humiliate him; I was not going to resign the way people wanted. But I wanted an exit strategy. It got to a point when I knew the man was really very sick. So, I needed out but I didn’t want to go the way others wanted me to go: to resign.

There was no foot in, no foot out. I had planned my exit strategy right from 2009. I wanted to leave and I had my plan. I told the presidency. Also, I saw my boss, I knew there was no way he could continue under the circumstances which he was in. I planned it so that in the next session, I would go to school. The school would be my excuse for leaving. That was my plan.

The belief was that First Lady Turai Yar’Adua called the shots in those last months of her husband’s presidency. She determined who had access to him in the Saudi hospital and who didn’t. Was it a failure of the constitution or the consequences of a poorly structured Presidency?

I think it was because we had never experienced that kind of thing before. And you can see that things are different now. We have learnt from it. Other countries have gone through that kind of experience. Read the story of America, you will see that they had a similar experience where a first lady was practically running the country. The challenge we had was, it was an unchartered territory. It is true that it was the first lady who could grant or deny access to her husband. And for me, that was fair enough. But the main problem actually arose because he didn’t write that letter. If he had submitted that letter – which he actually wrote; if he had submitted the letter empowering Jonathan to be the acting president, there would not have been an issue. Maybe the issue would have been, should he resign; should he not resign? There would not have been any constitutional problem.

Was the First Lady a shadow president?

There was no shadow president. She didn’t do anything when she came back. All the talk was just propaganda. All she did was protect the access to her husband.

Way before the health problems became magnified, there were stories about the influence she wielded within the presidency. Did she have that influence?

There was nothing. She was not running any show. Every wife has an influence on her husband. That is normal. But in terms of whether she was influencing government decision, I didn’t see any of such things. If she did, it was probably in the bedroom between her and her Husband. But that she went out and did anything openly, I never saw anything.

Goodluck Jonathan saw himself as a victim of the much talked-about cabal intent on ruling by proxy. When he was eventually sworn in as president, he cleaned house and got rid of all those that worked against him. Do you consider yourself a casualty of his house cleaning?

I was not part of any casualty. I resigned and I never worked against him. I resigned. I have my letter to him as acting president.

Do you really believe it that you weren’t pushed out?

No. It was because I got my letter of admission from Harvard and the thing had leaked. They wanted me to stay. Oronto (Douglas) had approached me. There are things I don’t want to say. I had no personal problem with Jonathan. In any case, if a new president came, what would I be hanging around to do? But the point really is that I had resigned 24 hours before my boss died, and everybody knew at the place.

Your book again, Power, Politics and Death comes across as an attempt to absolve yourself of any responsibility in how the president’s health and information about it was managed.

I gave my own account of what happened. There was no cover-up. I kept quiet. People expected me to speak, but, you know, a presidential spokesman speaks for the president. So if he didn’t authorize me to speak about his health, I couldn’t have gone out to speak about his health. Like now, ask Femi Adesina about Buhari’s health, he will not tell except Buhari authorizes him to speak. If I choose to hide my health status, my spokesman must hide it. He cannot go out and shame me.

So basically the president did not want you to speak on his health problems?

He never wanted it. I saw that he was very sensitive about his health. Anytime the issue of his health came up, I saw the way he usually reacted to it, even if it was about a report concerning his health. It made him look worried and I sympathized with him. That is what I saw.

This was a period when the political tension in the country was at boiling point. And in that atmosphere of fear and uncertainty where rumours were rife, a lot of things would have been happening that even you were unaware of. At a point, the U.S. Ambassador Robin Sanders put pressure on the then chief of army staff, Abdulrahman Dambazzau, to keep the military at bay. Did that threat of a military coup really exist?

I don’t know about the Sanders talk because I was very close and I am still very close to Dambazzau. The point though is that there were fears. Some governors in some of their meetings were saying it that there could be a coup if there was no political solution to the problem at hand. But most of those that were saying it were coming from the side of the people that were supporting Jonathan, dangling it as the reason why the issue should be resolved. So you can’t really know how genuine those reports were. But there were stories then that there could be a coup.

Coming to the 2015 presidential election, you took a very curious position. You wrote about close friends urging you to endorse Buhari, but somehow you couldn’t bring yourself to do it, why?

Did I write that? I don’t remember, but I didn’t endorse anybody. However, it was clear that I was opposed to Jonathan returning. I couldn’t bring myself to endorse Buhari because I really didn’t feel very comfortable with him. There were some issues I found difficult to reconcile. That is why I didn’t vote. At the time, if I had had to vote, I would have voted Buhari because I wanted Jonathan out. I believe we couldn’t continue the way we were.

In the election in 2015, the stakes were really high and Nigeria was on edge. Do you think that was a period for you to have sat on the fence?

I didn’t sit on the fence. It was clear that I was opposed to Jonathan returning; very clear. Jonathan’s people were attacking me. It was clear that I was not for the status quo. I just could not bring myself to support the change. But by inference, I supported a change and I have no regret for the position I took.

Going through your articles, it seems more like you were writing on what Jonathan had done wrong, what he could have done right, rather than not wanting him to continue. Is that so?

It is very clear I was very critical of him. Who would benefit from my criticism of his administration? It was the opponent. But I didn’t know what the opponent was bringing, so I could not endorse him. If I had endorsed Buhari, some people would be querying me. But I was saying we could not continue like this. And I defended Buhari when they brought the issue of his certificate and all that. I mean, at critical points, I made sure I was level headed in my approach to issues. I didn’t want to be deeply partisan.

But the stakes were way too high for anyone not to come out publicly with a position in that election.

I wrote on practically all the 36 states. I took positions on the states. On the federal, I couldn’t bring myself to endorse Buahri, but I was opposed to Jonathan.

It wasn’t until after the election that you said it would have been hypocritical of you to say you wanted Jonathan to continue. Do you think that was hypocritical?

I was critical of him. It would have been hypocritical to say this guy …it’s like the letter written on Magu at the Senate. One letter says this, this and this, you cannot endorse this guy. And the second letter, on the same platform, says we don’t mind if you endorse this guy. I stated clearly my points of departure with the Jonathan administration. I think, in the end, I just couldn’t bring myself to support the continuation of Jonathan in power. But at the same time, I didn’t endorse Buhari.

You never said it publicly that Jonathan should go, until after the election. Isn’t that hypocritical?

If you read my series on the election, it was clear I was opposed to the continuation of Jonathan. I didn’t say it. I didn’t write, ‘Don’t vote Jonathan’. No, I didn’t take that kind of position, but my

position was very clear. They knew I didn’t support them.

James Ibori is back in town. Convicted for corruption in the U.K., he was safe from prosecution under Yar’Adua. In fact, according to you, he pulled the strings in the anti-corruption fight. He may even have handpicked the attorney-general. Was the Yar’Adua compromised from the beginning?

I don’t want to speak on the issue; I have written about it. I don’t want to speak beyond what I have already written. He has served his term.

What is the central message of your new book, Against The Run Of Play?

The central message, really, is: one, an incumbent president can be defeated in Nigeria and, two, presidents will also be judged by their stewardship. I believe the 2015 presidential election was not so much a vote for Buhari, for majority of the votes were against Jonathan. It was more a referendum on the incumbent. That will help our democracy as we go. That, for me, was the message.

So you don’t think the votes were in support of Buhari?

There were votes for Buhari, but there were also votes for Buhari as a result of the rejection of Jonathan. In the south west, for instance, most of the votes were more against Jonathan than for Buhari.

Why did you decide to write the book?

I have always been interested in writing books, especially about the political process. My first book was in 1991. I was covering the (SDP). I was a reporter at The Guardian and before the primaries I wrote my first book, Before The Verdict, which I profiled all the presidential aspirants in the SDP. I used my money, all my savings. That time, it was self-publishing. I remember afterwards, the only person, it was Dr. Ibrahim Datti Ahmed who gave N4,000. I saved that money. And when the 23 aspirants of the two parties, both the Social Democratic Party and the National Republican Convention , were disqualified, I now revised the book. I rewrote it as Fortress On Quicksand in which case I profiled all the 23 aspirants in both SDP and NRC. That was my first major book as it were. Then after that, during the June 12 crisis, I followed the debate. I went to the National Assembly, I collected all the relevant documents, extracted the debateon June 12. That was what I polished as Politricks: National Assembly Under Military Dictatorship. It included all the debates about whether Babangida should go or not go. That was the second book. Then in 1994, I wrote Abiola’s Travails, when Abiola was in detention. I wrote it to mark his 60th birthday. The first book that was financially rewarding for me was The Last 100 of Abacha. I wrote it then to dissuade Obasanjo from third term. That time I was writing a series in my Column, that some of the people that were urging Abacha to contest were some of the same people asking Obasanjo to do a third term. Many people were interested. Many people had even forgotten. Someone came with the idea of a book. And a friend said, if you write a book, we

would publish it. I wrote the book. The guy agreed that when we publish it, we will share the profit 50/50. That was Book House. I wrote the book and I made a lot of money from it. That told me that I could be writing books. It was actually one of the reasons I turned down the offer when Yar’Adua offered me. I turned down the job for more than one month. I knew when I was going into government that I would write my experience. I didn’t know it was going to end in a dramatic fashion. I didn’t know that my boss was going to die, which made it even more compelling for me to document my experience. And that was what I did. For this election, it was the first time an incumbent was defeated. It is a story that is worth telling and I decided I was going to tell it. And I decided that, in telling it, I will speak to the principal characters, which is what I did.

Which aspects of it do you anticipate might trigger the most controversy?

I don’t know. I don’t think any would because it is not a book I just sat down and wrote. I spoke to many of the major characters. I went back, I corroborated; if I got new information, I went back again. There will always be controversy for a book of that nature.

Has your phone stopped ringing?

No. My phone has not stopped ringing. My phone was ringing while I was in office and it is still ringing now. I still keep my friends; I never left my friends, my genuine friends when I was in office. And they didn’t abandon me either, in or out of office.