He is the closest thing to a Nigerian Desmond Tutu, a voice that can be depended upon to speak truth to power, however inconvenient.

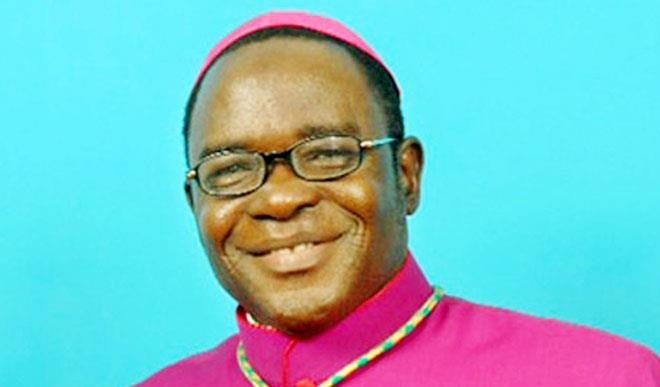

Yet, last year when we first contacted Bishop Mathew Hassan Kukah to grace the cover of the magazine, he demurred.

“You have featured a number of top religious figures, politicians and former heads of state,” Kukah said. “I think you should give people time to digest what is already out there.”

Kukah is right and wrong.

It’s true that every edition of The Interview provides the reader with more than enough to chew on; but a subject like Kukah brings a new perspective to even an old debate.

So, we pressed until he relented and opened the door of the Kukah Centre in Abuja, where we had the interview in December.

As a member of the Peace Committee that helped to ensure the orderly and peaceful transfer of power from an incumbent administration to the opposition in 2015 – the first such transfer in the history of the country – Kukah’s commitment to the success of President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration should be taken for granted.

But it wasn’t long after Buhari’s swearing-in that Kukah ran into a storm over his comment about the government’s approach to the fight against corruption.

The problem was not so much what he said as it seemed to be a nagging perception that he was pro-Jonathan, right or wrong.

Kukah insists that it was a perception motivated by hypocrisy and mischief. “Many of those claiming to love Buhari more than he loves himself today,” he said, “have no idea that I have built a relationship with him over the years based on openness and honesty.

“I’m not opposed to the war against corruption. My point is on strategy and process; going beyond the surface and the headlines. If Jonathan is found guilty of any crime, please let him face the music.”

The interview covered a wide range of issues; from politics to security and the use of religion by politicians to divide and rule.

Because of Kukah’s access to power, his relationship with past and present leaders also featured prominently.

In a country where access is often conflated with abuse and aggrandizement, men like Kukah are often, quite unfairly, held vicariously liable for the actions or inactions of every government in power.

Even when they are publicly at odds with the policies of such governments – as in the case of General Sani Abacha when the dictator used a private channel to shoo away the cleric – the public still somehow believes clerics ought to be able to use their ecclesiastical gifts to whip the wayward government in line.

Heads they lose, tails they lose.

But Kukah is not deterred; his faith leads him on. He has given so much to the conversation to secure and renew Nigeria’s place in history that his imprint lingers in many defining moments in the last three decades or more.

He played a major role in finding a consensus around the demands of the Ogonis over the degradation of their land. Kukah was the secretary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up by former President Olusegun Obasanjo.

He has also been front-and-centre in different national and international efforts to build religious peace and tolerance in the country.

Yet, it’s clear from this interview that his job is not done. Like Tutu, Leornado Boff, Jon Sobrino and a long line of his ecclesiastical forebears, the passion to lift up the poor and the dispossessed, to bring equity and justice in the exercise of power, is Kukah’s life.

And believe it or not, this assignment does not abhor “Sitting In Limbo,” a track from one of his favourite artistes, Jimmy Cliff.